|

Ingredients: For the Crust:

Stir together the crust ingredients in a bowl until completely combined. Press firmly into the bottom of an 8x8 square baking dish or a pie plate. Place in the fridge for at least 1 hour. To make the filling, place the room temperature cream cheese in a food processor along with the lemon juice, vanilla, honey and Greek yogurt. Process until completely combined and smooth. You can also use a hand or stand mixer. If you do beat the cream cheese first before adding all the other ingredients to avoid lumps. Pour the filling mix into the prepared crust, smooth out, cover and place in the fridge for at least 24 hours. Once the cheesecake has set slice, top as desired and serve immediately. Top with fresh berries or a fruit compote. Adapted from fooddoodles.com

0 Comments

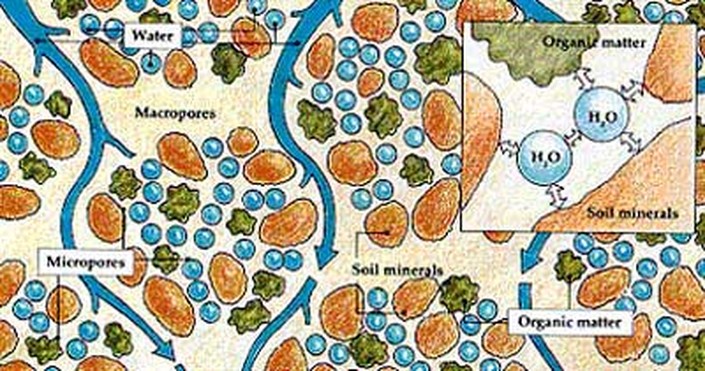

We want to thank all of you who came by for this year's Open Farm Day in Madison County. We had a great time sharing what we do with all of you, whether we're on the farming side of things, the creamery side, or both. We also want to thank Madison County Cornell Cooperative Extension for their continual efforts to help Madison County's agricultural businesses thrive. Events like this close the needless gap between our farms and our food, exhibit appreciation and support for our farmers, and strengthen our communities. Your participation is a step towards a better food system, and we're grateful for every step you take with us. From all of us at Kriemhild and Red Gate Farm: Thank You! This year, it seems to be that “April Showers” turned into May showers. And then June Showers. Now its July and the northeast still seems to be getting drenched at least twice a week. The constant thunderstorms and heavy rainfall is not just an inconvenience, but a danger as flash floods have become an occurrence around New York State. Even after the rainfall, the resulting influx of water is washing over roads, causing power outages, and even damaging homes. Farms struggle with heavy rainfall and flooding as well. Wet conditions force farmers to keep their heavy tractors out of the field to avoid getting stuck. Standing water from saturated soils or flooding can drown crops and pasture plants, both posing significant losses. Bruce and Nancy Rivington, Kriemhild co-owners and farmers of Red Gate Farm, own about 700 acres of contiguous land. Despite the inundation of precipitation since spring, none of their pastures had flooded this year. Now, this may be due to luck, but it is likely due to the impact grazing has on their soils. Climate Change is HereWe’ve discussed how the practice of grazing encourages carbon sequestration, but this is not the only way that grazing combats climate change. The Northeast United States has had a 70% increase in the amount of heavy precipitation events between the late 1950s and 2010, and winter and spring precipitation is predicted to only increase (1) . On the other side, as temperatures in the summer and fall increase, seasonal drought is projected to become more frequent (2). With these climate predictions, a farmer’s best choice is to cultivate a resilient soil that can handle both drought as well as heavy precipitation. The best way to insulate soils from the impacts of extreme wet or dry conditions is to develop a strong soil structure. Most are familiar with the importance of nutrients and minerals in soil, but without a structure in which water and air can move, plants have difficulty pushing their roots through the soil and accessing those nutrients. The structure of the soil is how the particles are held together, or aggregated. Grass naturally does a nice job of holding soils together with its fine root system and, if managed correctly, it also covers the soil and protects it from erosion. The Tiniest LivestockAs pasture plants photosynthesize, they create nutrients of their own that they excrete into the soil as exudate. Millions of microorganisms and mycorrhizal fungi, feed upon this exudate, a symbiotic relationship, and in turn bring nutrients to the plant. While this abundance of micro-life feeds on their exudate buffet, excrete waste, and eventually die, they create organic matter and other glue-like protein substances that hold soil particles together. This structure building allows micro and macro pores to manifest in the soil, making highways for air and water to travel to plants roots, micro critters and slightly larger soil inhabitants, such as worms, dung beetles, grubs and moles. A well-aggregated soil is made up of half pore spaces and half solid particles.

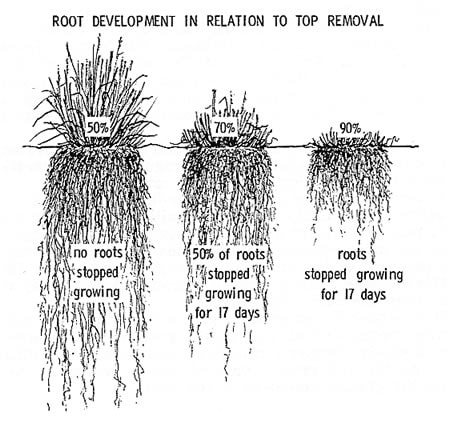

Bruce and Nancy’s grazing management is centered on soil health. Red Gate Farm’s perennial pastures’ roots run deep. The cows are allowed to graze each paddock down to a certain height, but then are rotated to a new field to give the grazed pasture plants time to rebound. When plants are grazed, they slough off a portion of their roots. These roots decompose and add to the soils organic matter. While the pasture rests, the plants regrow and their roots penetrate deeper into the soil, making passageways for air and water to reach to lower soil layers and while accessing nutrients stored in the depths. All along the way, microorganisms interact with the expanding root systems, creating more organic matter and “soil glue”, building a resilient soil structure that acts like a sponge. This system keeps Red Gate Farm dry when it rains, and green when it’s dry. It’s easy to get caught up in the individual health benefits of grass-fed and grass-grazed products and overlook the overarching natural cycles that responsible grass-based production perpetuates. It’s important to us to remember that our Meadow Butter is the result of a complex, thriving ecosystem - and we plan to keep it that way. So, join us at the Red Gate Farm on Open Farm Day as we dig deeper into how the Rivingtons’ cows turn pasture into your favorite Meadow Butter on July 29th. Cited Sources:

1. Groisman, P. Y., R. W. Knight, and O. G. Zolina, (2013) “Recent trends in regional and global intense precipitation patterns.” Climate Vulnerability, R.A. Pielke, Sr., Ed., Academic Press, 25-55. 2. NPCC, (2010) “Climate Change Adaptation in New York City: Building a Risk Management Response” New York City Panel on Climate Change 2009 Report. Vol. 1196C. Rosenzweig and W. Solecki, Eds. Wiley-Blackwell, 328 pp. It Took Some Convincing...Bruce and Nancy Rivington moved their entire farm and family of six from Ontario, Canada to Hamilton, NY in order to give their cows more chances to graze. But, just as Red Gate Farm wasn’t always a grazing farm , Bruce and Nancy were not always graziers. “I kind of made fun of it, [grazing]” Bruce explains, “It seemed stupid, why’d you want to do that when you could just… get more milk production by bringing the feed to the cows?” In Canada, the Rivingtons were content with growing, cultivating, and harvesting crops for the purpose of feeding to their herd. They had a plenty high milk production per cow. Why would they want to give up something they were good at? It wasn’t until they attended a talk by Sonny Golden, a grazing and nutrition specialist from Springfield, PA, that the Rivingtons began to examine their management choices. “He says, ‘You plant corn. What grows? Grass. You plant soybeans. What grows? Grass. You plant barley. What grows? Grass! Why aren’t you growing grass?!’ Which made a lot of sense.” Bruce reminisced. Bruce and Nancy realized they were producing a large quantity of milk, but the costs of such high production were taking their toll. As Bruce remembers, “We were hauling all the feed to the cows, but we were wearing out ourselves, our cows, the machinery, the barn.” Therefore, the Rivingtons decided to try to work within the naturalized system of pasture and ruminant animals, instead of against it, and began practicing grazing in 1994.

Grazing has more than just financial benefits. It improves the quality of life for the cows. In addition to the health benefits of eating fresh grass, they get to engage with their herd mates and the environment naturally as they enjoy the outdoors. When carefully managed, grazing can improve or maintain environmental health as well, through increasing soil health, biodiversity, and even carbon sequestration.

Most pasture plants have evolved to be grazed, and there are dozens of species of grass, fescue and legumes that a cow can choose from. Grazing actually stimulates these plants' growth. Yet, if grazed too short, pasture plants struggle to capture energy from the sun and must move their stored resources in their roots to grow new leaves. Being grazed too short, or too often, time after time will deplete the plant’s energy reserves, leaving an unproductive pasture, and even plant death. However, depending on the season, weather, and the type of plant, grass will grow at variable speeds. In order to maintain the health of the pasture, so that it remains productive in future seasons, the Rivingtons must pay attention to these changes and adjust their grazing plan accordingly. They may give a section of field a longer time to recover based on how quickly it is regrowing, or put the cows in a larger section so the pressure of grazing is spread thinner over the field. The Positive FeedbackBy keeping up this management, the Rivington family and their farm team maintain a positive feedback loop that builds soil and grows nutrient dense grass for their cows. The Rivingtons also enjoy the benefits of not having to purchase and handle certain petroleum based inputs, such as pesticides, herbicides or fertilizer. Practicing grazing means much more time spent in the fields, retrieving cows for milking, moving fencing, or just watching the grass grow - all of which is pretty good exercise (If you don’t believe us, just try racing Bruce up his favorite pasture hill).

It is true - their cows don’t make as milk as they used to on grain, but the Rivingtons have found a system that is attuned with their values and gives them a lifestyle that suits their family, their farm team, their pastures, their cows, and you, our customers. Don’t just take our word for it, visit the farm on Madison County’s Open Farm Day to experience the joy of a grazing dairy yourself. We’ll have tours, activities, and, of course, plenty of Meadow Butter. Ingredients:

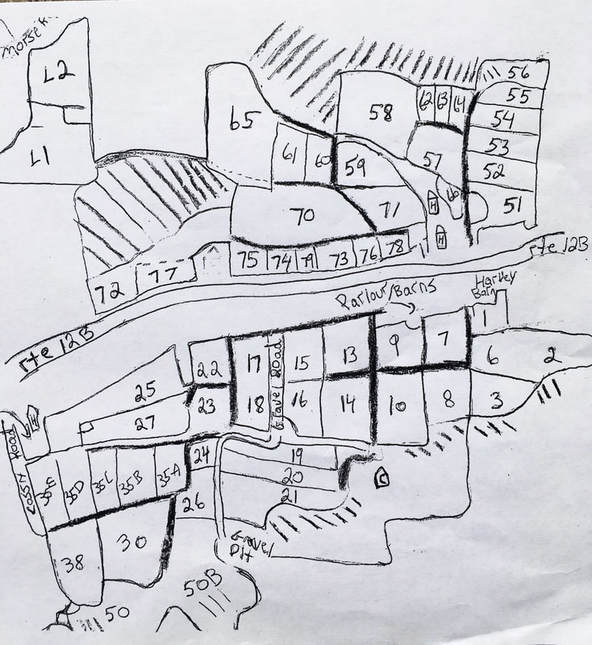

Instructions: Combine vegetable oil, thyme, and Dijon mustard in a large bowl and mix together. Season the meat with salt and pepper and toss in the marinade, cover and refrigerate 4 hours or overnight. Remove the meat from the marinade. Reserve the marinade. Heat 1 tablespoon butter in large, deep-sided sauté pan over medium heat. Add the scallions and garlic. Season with salt and pepper and cook until tender, about 5 minutes. Remove from the pan. Add a tablespoon of butter, and brown the meat pieces on both sides, about 2 minutes per side. Deglaze the pan with the champagne vinegar. Add the chicken stock and the residual marinade in the bowl. Cover with a piece of parchment paper and then a lid. Cook over the lowest heat , about 20 minutes. Flip the meat over. Cover with parchment and lid and continue cooking 10 minutes. Add the scallions. Then cook until the meat is done, about 20 minutes. Remove the meat from the pan and cover to keep warm. Reduce the sauce until it coats the back of a spoon. Stir in half the tarragon and creme fraîche. If the sauce seems too watery, put the pan back on the heat and reduce it until it is thick. While the sauce is reducing, heat the remaining tablespoon of butter in a small sauté pan over medium heat. Add the radishes and brown all over. Season with salt and pepper. Add the radish leaves, toss and then add the peas, honey, the remaining teaspoons of vinegar and remaining tarragon and toss to coat. Recipe adapted from hegarumfactory.net If you haven’t learned by now, Kriemhild Dairy is intimately connected with Red Gate Farm, our sole seasonal Meadow Butter supplier. Farmers Bruce and Nancy Rivington own 90% of Kriemhild and have had an essential role in developing our values and guiding the direction of our small agricultural business. In fact, we all would consider being able to access and experience the farm a job perk: we get to interact with their beautiful, and curious, herd of cows, have walking privileges to the rolling pastures, and occasionally get roped into doing some farm work. You, or someone you know, might even be familiar with the farm. Kriemhild and Red Gate Farm often collaborate on farm events to encourage people to engage with the staff and animals who contribute to the production of their food. Red Gate hosted its first Calving Day this year, but many visitors’ first experience of the Farm is during Madison County’s Open Farm Day. Red Gate Farm has been participating in Open Farm Day for the 8 years the event has existed, this year will be no different. But, likely unbeknownst to visitors, 17 years ago, Red Gate’s rolling green pastures looked very different than they do today. From Canada to CNYWhen the Rivington Family moved from their dairy farm in Ontario, Canada to New York, they were on a clear-cut mission: to graze. The Rivingtons wanted to increase the amount their cows could graze, and ultimately switch to seasonal dairying for human and herd wellbeing. Although the Canadian supply management policies promised consistent revenue for Canadian dairy farmers, the system would not accept the variable amount of milk produced by a grazing seasonal dairy. With aspirations of expanding their farm and embracing seasonal grazing, the Rivingtons began to search the Empire State for their new home. Nancy and Bruce visited about 18 different farms hoping to find one that was suited for grazing. Mainly, they were searching for at least 400 acres of contiguous land so as to make it possible to move a herd easily from one pasture to the next. This was more of a challenge than expected. “Real estate agents have real funny definitions of contiguous,” Bruce recalls. It was in the depths of winter when the Rivingtons were introduced to Red Gate Farm. Although the land was buried in snow, the Rivingtons knew it was the farm they were looking for. They bought the farm in 2000. Red Gate Farm was a dairy farm historically, but most of its 512 acres had been in conventionally managed corn and alfalfa crops for almost 3 decades. Although rotating corn and alfalfa crops is an effective practice for those who strive to grow an abundance of those two crops, this type of management can take its toll on the land. Bringing Back The Grass Growing a single or limited amount of crops on the same land quickly depleted the soil of its fertility, making it necessary to apply chemical fertilizers to just as quickly supply the exact amount of nutrients the crop needed. Repeated tilling and cultivating also deteriorated the soil. This practice released soil nutrients into the air and broke up the roots and aggregates that held the soil together, increasing the rate of erosion. Bruce remembers discovering the poor condition of the soils, “When we first bought the farm we had to hunt to find an earthworm.”

Despite its sorry condition, Bruce and Nancy knew the healing effect that grazing could have. So, the Rivingtons gave the Red Gate Farm fields their last tilling ever, only to plant an abundance of perennial grass seeds. Starting with a small herd, they gently grazed and mowed the grass to encourage root growth and carbon sequestration. After 5 years of careful and nurturing management, Red Gate Farm began to resemble the farm we all know today: 737 acres of lush green grass carpeting miles of land speckled with colorful moseying cows grazing at their leisure. Even the section of field burned with pesticides was regenerated, and now is ironically one of their most productive pasture, growing almost exclusively native grasses. “That’s the pasture I like to take people up to, to show them,” Bruce boasts. Land that Doesn't Just Work, But LivesThe Rivingtons did not merely transition Red Gate Farm from one crop to another. They reclaimed land stripped of its nutrients, only able to grow corn and alfalfa, and regenerated it into a thriving ecosystem. Their land not only grows nutrient dense grasses, but it also feeds an expansive community of soil microbacteria and microfauna, acts as a habitat for wildlife, and even mitigates greenhouse grasses.

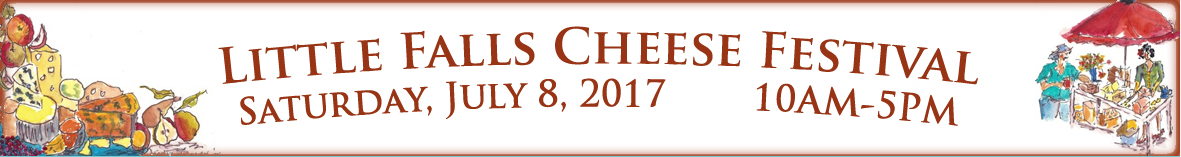

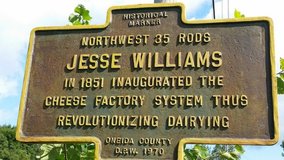

Although this happened long before Kriemhild was established, we would not exist without Red Gate Farm, so we embrace it as part of our story. We hope to help other farmers tell their own similar stories as we grow. Until then, you can visit Red Gate Farm on July 29th as we celebrate Madison County’s Open Farm Day. It’ll be a great chance to learn more about how agriculture can be a pivotal point of community, nutritional, and environmental health. On July 8th, we will be attending and vending at the 3rd annual Little Falls Cheese Festival in Little Falls, NY. We have been diligent participants of the festival since its debut in 2015, but we still have yet to sample all the cheeses the event has to offer. In addition to a wide regional selection of artisan and farmstead cheese, the festival also features all things cheese-complementary, including, but not limited to: gourmet chocolates, artisan breads, pastries, spreads, and, of course, butter. As much as we love the abundance of artisan foods, live music, and good company that we experience throughout the day, what touches us the most is what the festival celebrates: the rich history of pioneer creameries and dairy food manufacturing in New York State. Herkimer Cheese Although Wisconsin and California are currently fighting for the title of largest cheese manufacturer in the United States, throughout the 19th century New York was the leading state in amount of creameries, with Little Falls, in Herkimer County, NY as its cheese capital. Due to the fame of Herkimer County Cheese, the first United States cheese exchange was hosted in Little Falls in 1850s, set the price of cheese for the country, and even influenced the cheese prices in Europe.  Multiple factors allowed Herkimer County to rise up as the cheese center of the United States. New York’s climate, which is ideal for grazing dairy cattle and making cheese and butter, and Jesse Williams who pioneered the “cheese factory” system. Before the cheese factory, cheese and butter making was essentially the work of farm wives and dairy maids. While the task was arduous and at times resulted in inconsistent cheese quality, skilled dairy maids could provide for their families with their craft. The first cheese factory in America was established in Rome, NY in 1851 after Jesse Williams, dairy farmer and cheesemaker, began processing milk delivered from his son’s dairy farm alongside his own to make cheese. Although milk cooperatives are common today, in the 1800s, this practice was novel. Jesse went on to accept more deliveries from other farms in the area and institute an efficient system of milk collection as well as consistent quality cheesemaking. The switch from farmhouse to factory cheesemaking empowered dairy farmers and manufacturers to produce over 49,000,000 pounds of cheese in 1850, compared to Wisconsin’s mere 400,000 pounds. In 1899 at least 1,611 factories in NY made either cheese or butter, 207 of which made both. Goshen Butter About 170 miles south of Little Falls, New York butter was having its heyday as well. In 1856, the first factory in the world specifically built to manufacture butter was built in Campbell Hall, Orange County, NY. Being constructed in the pre-refrigeration era, the creamery’s placement relied on the existence of a natural cold spring with which the butter was chilled. As with New York cheese, it was skilled farm wives and dairy maids who made butter popular in Orange County. These farmstead producers were already the main suppliers of butter to New York City which were delivered regularly by way of horses and carts. The butter of Orange County was famously known around the country as “Goshen Butter”. However, the ability to produce large quantities of butter of consistently high quality left the Campbell Hall butter factory responsible for New York State’s peak in butter production from 1860 to 1890. Ultimately, New York’s Herkimer Cheese and Goshen Butter faced the same sad fate. As refrigerated transport made it possible to ship fresh milk to New York City and other urban areas, the need for shelf stable dairy products sharply declined. Between 1890 and 1910, the production of New York butter decreased 80%. New York's Dairy Comeback

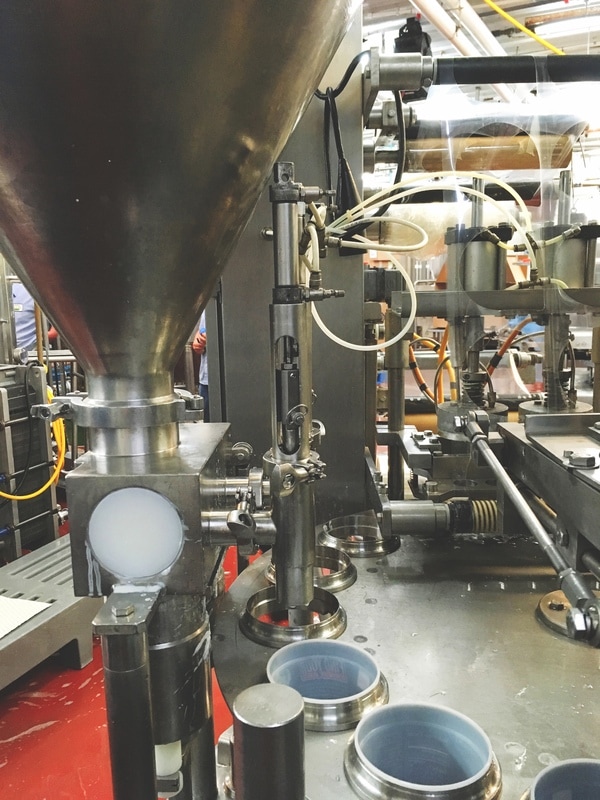

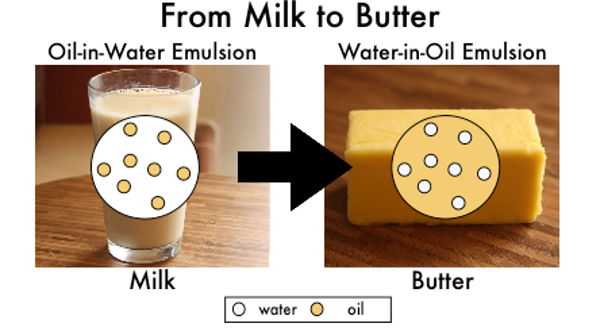

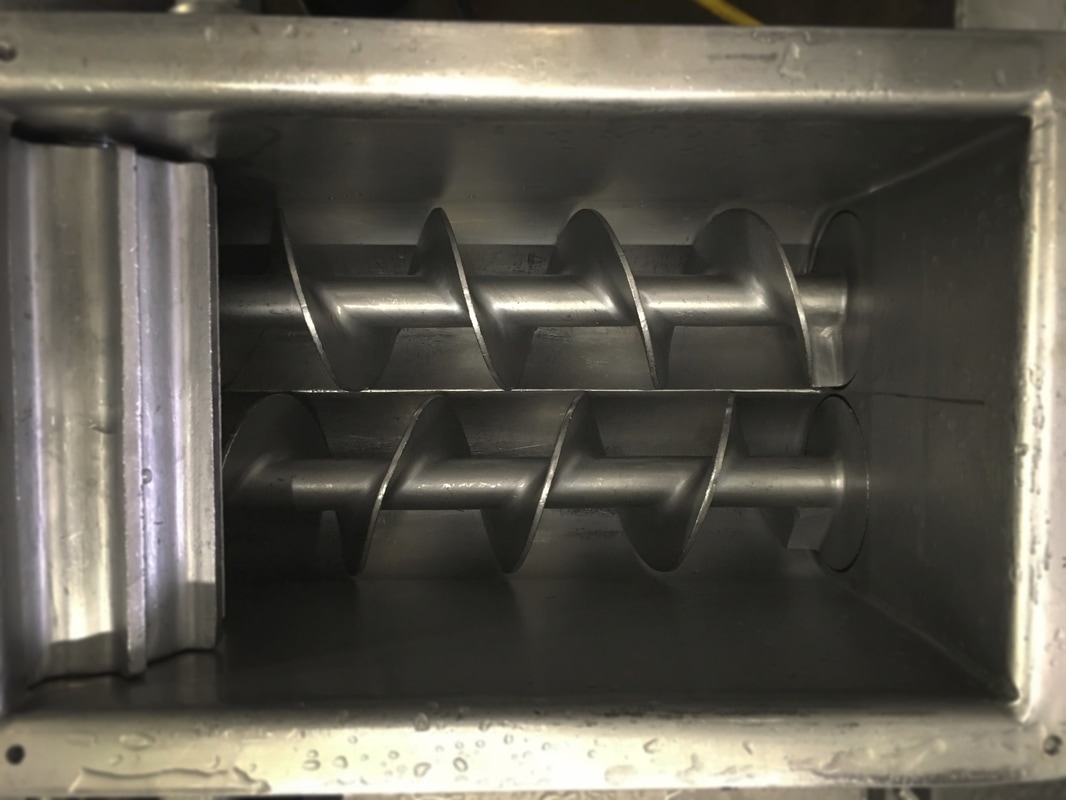

As much as the Little Falls Cheese Festival observes New York’s rich cheese production history, it is also a celebration of the revival of the state’s artisanal dairy crafters and small dairy industry. Although no longer the top producer of cheese and butter, dairy farming is still the leading agricultural industry in New York state. Entrepreneurs are taking advantage of New York’s abundance of quality milk and getting creative with it. Increasingly, farmers are bottling, branding, and marketing their own milk, small businesses are opening small batch creameries and making value-added products, and processors are collecting local milk from small dairies and using it to co-pack for national brands. As of now, New York State is the lead in yogurt production in the nation and its dairy manufacturing industry employees over 8,000 workers. In addition to feeding the economy, New York small dairy processors and dairy artisans are telling their farmers’ stories (if they’re not the farmer themselves) and responding to a growing consumer base that expects transparency, environmental stewardship, and quality by striving to create food that reflects those values. This is our mission at Kriemhild and we have joined many other fellow dairy processors that follow similar paths. It is true, the landscape of New York’s dairy industry has changed. But, as long as there are dairy farmers, there will be processors, and New York’s dairy will be rich. Sources: Sernett, Dr. Milton C. Say Cheese!: The Story of the Era when New York State Cheese was King. Cazenovia: Milton C. Sernett, 2011. "Governor Cuomo Announces New York State is Now Top Yogurt Producer in The Nation, Delivers on Key Promises Made at Yogurt Summit to Help Dairy Farmers." The Official Website of New York State. 18 April 2013. www.governor.ny.gov. Taking The Next Step When we became ready to expand the Kriemhild brand and develop another product we searched our stomachs for something unique but also something that echoed the qualities of our butter: high butterfat percentage, full fat, and grass-grazed. We settled on crème fraîche, our cultured heavy cream. To turn this dream into cultured cream, we needed the help of our second dairy co-packer: Sunrise Family Farms in Norwich, NY. Opened for business in 1999 by Dave and Susan Evans, Sunrise Family Farms collects milk from multiple dairy farms, organic and conventional, in the surrounding Chenango County area, processes, and packages it for over 10 different private dairy labels. Sunrise Family Farms is neither a large manufacturer, nor a tiny one. This mid-size operation makes it possible for them to serve national brands, and at the same time package for smaller local brands (like us!) allowing them to grow their production and diversify their product line. The creamery currently runs multiple shifts, 24 hours a day, and employs a team of more than 50 dedicated workers. Being familiar with their high-quality yogurts, and with their availability of local, grass-grazed cream, Sunrise Family Farms was our go-to for co-packing our crème fraîche. Getting Cultured The process for making crème fraîche is similar to making yogurt or sour cream, but even more simple. When the milk arrives to sunrise family farms, it is pasteurized at a high temperature, 161 degrees fahrenheit, for a short amount of time, 15 seconds. This technique, known as high temperature short time (HTST), is the most common method of pasteurization in the dairy industry. (It is a separate method from Ultra pasteurization (UHT), which holds milk at 280 degrees fahrenheit for 2 seconds or vat pasteurization which holds milk at 145 degrees for 30 minutes) After pasteurization, milk intended for crème fraîche production is held at 80 degrees fahrenheit. The cream is separated using a centrifugal cream separator, and the remaining skim milk is used to produce other products within the facility. The cream is moved to a vat, and a mix of cultures is added. The mix of cultures is different from yogurt. The main cultures in yogurt, Lactobacillus bulgaricus and Streptococcus thermophilus, are heat loving bacteria. Therefore, when making yogurt, the milk is fermented between 110 and 115 degrees fahrenheit. The cultures in crème fraîche include L. cremoris, L. lactis, and L. biovar diacetylactis, and often others. When these bacteria are added to cream, they consume the lactose, the sugar found in milk, and convert it into energy leaving lactic acid as a byproduct. The lactic acid decreases the pH of the cream, making it inhospitable to other competing bacteria that encourage spoilage, and changing the flavor. It is L. biovar diacetylactis, specifically, that produces the buttery flavor you know to be distinctive of crème fraîche. After the culture is added, the cultured cream is sent through a pipe into a rotary filler that fills and encloses individual tubs. As the units come off the filler they are brought to a well ventilated incubating room that is held at 80 degrees fahrenheit as the cream “sets”. As the pH decrease due to the increased production of lactic acid by the live bacteria, proteins in the cream begin to unfold. This process thickens the cream as it incubates from 12 to 18 hours before it is packaged, refrigerated, and then picked up by Kriemhild. Co-packers are essential to the dairy industry Even though you might buy a national brand, local co-packers can make it possible that the milk in your food is sourced from local farmers. For smaller businesses, like us, co-packers can be a significant stepping stone on the way to their own processing facility. Sunrise Family Farms, in particular, serves as an important outlet for a dairy rich region and provides jobs in an otherwise economically struggling area. As a fellow small business, we are proud to have Sunrise Family Farms as our co-packer. We both strive to support family dairies in our community. This June, we are inviting you, our customers, to join us in celebrating National Dairy Month - an annual tradition that acknowledges the contributions of the dairy industry to our health, our communities, and our environment. Originally created as National Milk Month in 1937 for the purpose of promoting the sale of milk, the National Dairy Council changed the name as the public embraced the opportunity to recognize the significant role that all dairy farmers and processors play in the food system. As a dairy processing business, we would like to celebrate National Dairy Month by highlighting the...well...process of turning local milk into your favorite Meadow Butter and Crème Fraîche. This week we will be shedding light on the details of our Meadow Butter production. Why Butter? When Kriemhild Dairy Farms was established in 2010, we were already committed to the advancement of grazing dairies and the creation of high-quality, grass-grazed dairy food. The flavor and nutritional benefits of grass-grazed dairy products manifest the the best in high-fat products. Therefore, when Kriemhild was developing its first product, butter was a natural choice, and ultimately became our signature creation. Our Co-Packer However, as a start-up agribusiness, we would not have been able to create our Meadow Butter without the unique partnership we have with our co-packer, Queensboro Farm Products in Canastota, NY. At the time of our founding, the farmers who founded Kriemhild -- including co-owners Bruce and Nancy Rivington, owners of Red Gate Farm -- were already shipping their milk to Queensboro. They were aware that Queensboro had a reputation for making butter with a higher than average butterfat, so it was a perfect place to begin our butter production. A typical relationship with a co-packer implies the employees of the facility handle all of the production and packing of a product for an external company. Our relationship with Queensboro, is atypical in that we, as a company, physically take part in the production and packing of our butter within the facility using a combination of both our own and Queensboro’s equipment. Making Dreams Out of Cream Red Gate Farm’s grass-fed milk is picked up and delivered by a trucking service and sold to Queensboro Farm Products every other day. The cream is separated from milk using centrifugal cream separator. This process, which takes about 24 hours naturally, only takes about 13 minutes. The remaining skim milk is sold on the general milk market or used to make other Queensboro products. The cream, which is approximately 38% fat, is pasteurized and transferred to a vat to temper. During the tempering process, between 18 and 24 hours, the fat globule restructures itself and continues to release latent heat. Once the cream has tempered, it’s then piped into a barrel churn. 42,500 pounds of Red Gate Farm’s milk will yield approximately 2,000 pounds of butter, however, this number will vary depending of the percentage of butterfat in the milk. The churn is a mechanical barrel that will spin about the speed of a clothes drying machine, tumbling the cream. The agitation of the cream disturbs the hydrophobic phospholipid membranes surrounding the milkfat globules. As Dr. Robert Bradley likes to describe it in his book, ‘Better Butter’: "Cream is an oil-in-water emulsion that turns into butter when inverted to a water-in-oil emulsion." After about 45 minutes of churning, small clumps start to form, a state known as “popcorn butter” or “butter grains”. At this point the whey is drained, the butter rinsed, drained again and the butter is sold and turned over to Kriemhild. As a team, we don hair nets, plastic aprons, clean rubber boots, and disposable gloves to prepare for a day of packing butter. We begin by doing a complete wash of all our equipment. If we are making salted butter, salt is added to the “popcorn butter” and then it is put through about another five minutes of churning. The fat globules that form the small clumps continue to fuse to each other, pushing our air and moisture, to a point where it is a single creamy, firm mass of butter. We use a mix of technology and elbow grease to pack our butter into different sized containers. All the butter is taken from the churn and placed in a low sheer pump with two strong metal augers that push the butter through a round pipe, similar to a play-doh factory toy. As the butter comes from the pipe it is cut to a certain size, placed on wax paper, and hand rolled to create our traditional rolls. Our two pound, five pound, and 50 pound sizes are also all hand packed. The only size not hand-packed is our 8oz container. To fill our half-pounders, our butter pump is connected to a rotary filler which directly fills our screen printed tubs to an accurate weight, places and heat seals a piece of foil to the top, and presses a lid to close it. When all the butter is packed in containers, it’s then put into labeled boxes for either direct delivery to one of our wholesale accounts or for storage until later. Then, the whole production room and equipment need to be rinsed, washed, and sanitized again. Depending on the size of the batch of butter, and the sizes of units we are packing, a day of butter production can last from 4 to 8 hours. This does not include the time it takes to load the pallets of boxes onto our refrigerated truck, travel back to our headquarters, and then unload and organize our inventory. Food production is also physically intense. It involves standing on hard ground for long hours, tedious periods or repetitive motions, lifting and moving heavy boxes, and no matter how hard we try to not get wet, we always get wet during washing. From Our Hands to Yours Food processing is hard work, but we love to be able to see the creation of our butter from pasture through to market. And although our reach is far, and growing, when you meet one of our team, whether they're delivering your order or at the farmer’s market, you can know that team member handing you your butter is the same person who has taken part in making it. INGREDIENTS

Preheat oven to 300°F. Whisk together flour, salt, baking powder, and rosemary in a bowl. Mix together butter, honey, and confectioners sugar in a large bowl with an electric mixer at low speed. Add flour mixture and mix until dough resembles coarse meal with some small, pea-sized butter lumps. Gather dough into a ball. Knead dough on a lightly floured surface until it just comes together, about 8 times. Halve dough and form each into a 5-inch disk. Roll out 1 disk between 2 sheets of parchment paper into a 9-inch round. Remove top sheet of parchment and transfer dough on bottom sheet of parchment to a baking sheet. Score dough into 8 wedges by pricking dotted lines with a fork. mark edges decoratively. Arrange rosemary sprigs decoratively on top of dough. Sprinkle dough with 1/2 tablespoon granulated sugar. Bake shortbread in middle of oven until golden brown, 20-25 minutes. Slide shortbread on parchment to a rack and cool 5 minutes. Transfer with a metal spatula to a cutting board and cut along score marks with a large heavy knife. Make another shortbread with remaining dough. From Epicurious.com |

As the Butter Churns

Author: Ellen Fagan and Victoria PeilaCategories

All

Archives

November 2019

|

Where our HEart is

|

FOLLOW US |

what our customers are saying"Thank you! Even though I'm 5 hours away...I can't live without you. Got my shipment today.

#kriemhildbutterlove" -- Jennifer in Mystic, Connecticut |

Copyright 2020 © Kriemhild Dairy Farms, LLC

RSS Feed

RSS Feed