|

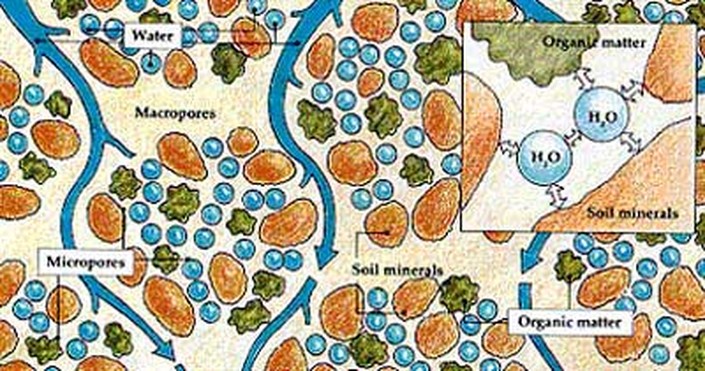

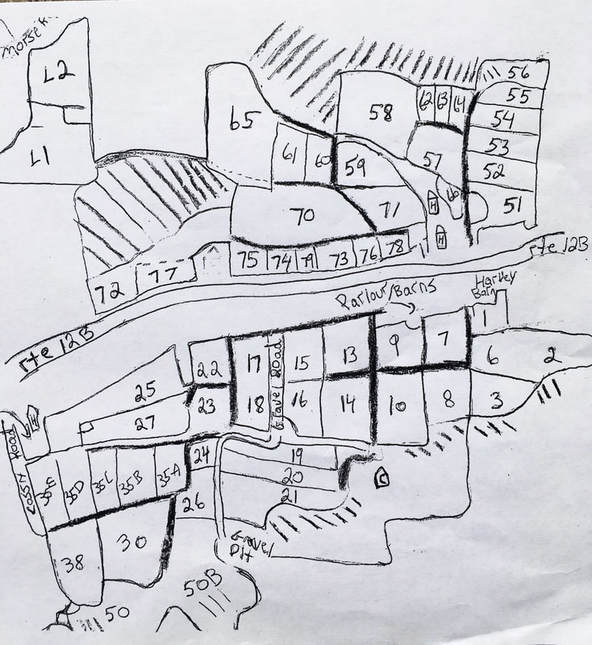

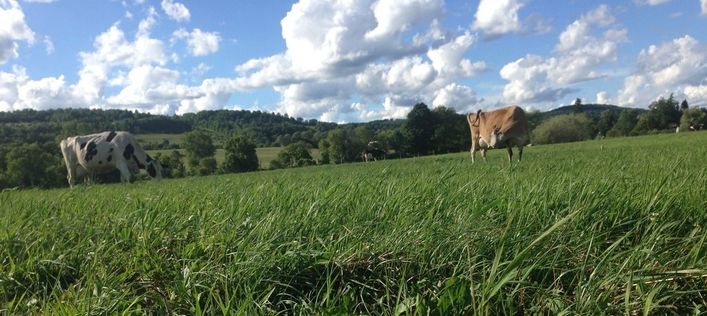

This year, it seems to be that “April Showers” turned into May showers. And then June Showers. Now its July and the northeast still seems to be getting drenched at least twice a week. The constant thunderstorms and heavy rainfall is not just an inconvenience, but a danger as flash floods have become an occurrence around New York State. Even after the rainfall, the resulting influx of water is washing over roads, causing power outages, and even damaging homes. Farms struggle with heavy rainfall and flooding as well. Wet conditions force farmers to keep their heavy tractors out of the field to avoid getting stuck. Standing water from saturated soils or flooding can drown crops and pasture plants, both posing significant losses. Bruce and Nancy Rivington, Kriemhild co-owners and farmers of Red Gate Farm, own about 700 acres of contiguous land. Despite the inundation of precipitation since spring, none of their pastures had flooded this year. Now, this may be due to luck, but it is likely due to the impact grazing has on their soils. Climate Change is HereWe’ve discussed how the practice of grazing encourages carbon sequestration, but this is not the only way that grazing combats climate change. The Northeast United States has had a 70% increase in the amount of heavy precipitation events between the late 1950s and 2010, and winter and spring precipitation is predicted to only increase (1) . On the other side, as temperatures in the summer and fall increase, seasonal drought is projected to become more frequent (2). With these climate predictions, a farmer’s best choice is to cultivate a resilient soil that can handle both drought as well as heavy precipitation. The best way to insulate soils from the impacts of extreme wet or dry conditions is to develop a strong soil structure. Most are familiar with the importance of nutrients and minerals in soil, but without a structure in which water and air can move, plants have difficulty pushing their roots through the soil and accessing those nutrients. The structure of the soil is how the particles are held together, or aggregated. Grass naturally does a nice job of holding soils together with its fine root system and, if managed correctly, it also covers the soil and protects it from erosion. The Tiniest LivestockAs pasture plants photosynthesize, they create nutrients of their own that they excrete into the soil as exudate. Millions of microorganisms and mycorrhizal fungi, feed upon this exudate, a symbiotic relationship, and in turn bring nutrients to the plant. While this abundance of micro-life feeds on their exudate buffet, excrete waste, and eventually die, they create organic matter and other glue-like protein substances that hold soil particles together. This structure building allows micro and macro pores to manifest in the soil, making highways for air and water to travel to plants roots, micro critters and slightly larger soil inhabitants, such as worms, dung beetles, grubs and moles. A well-aggregated soil is made up of half pore spaces and half solid particles.

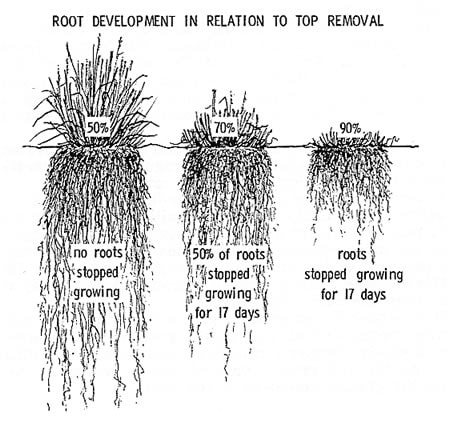

Bruce and Nancy’s grazing management is centered on soil health. Red Gate Farm’s perennial pastures’ roots run deep. The cows are allowed to graze each paddock down to a certain height, but then are rotated to a new field to give the grazed pasture plants time to rebound. When plants are grazed, they slough off a portion of their roots. These roots decompose and add to the soils organic matter. While the pasture rests, the plants regrow and their roots penetrate deeper into the soil, making passageways for air and water to reach to lower soil layers and while accessing nutrients stored in the depths. All along the way, microorganisms interact with the expanding root systems, creating more organic matter and “soil glue”, building a resilient soil structure that acts like a sponge. This system keeps Red Gate Farm dry when it rains, and green when it’s dry. It’s easy to get caught up in the individual health benefits of grass-fed and grass-grazed products and overlook the overarching natural cycles that responsible grass-based production perpetuates. It’s important to us to remember that our Meadow Butter is the result of a complex, thriving ecosystem - and we plan to keep it that way. So, join us at the Red Gate Farm on Open Farm Day as we dig deeper into how the Rivingtons’ cows turn pasture into your favorite Meadow Butter on July 29th. Cited Sources:

1. Groisman, P. Y., R. W. Knight, and O. G. Zolina, (2013) “Recent trends in regional and global intense precipitation patterns.” Climate Vulnerability, R.A. Pielke, Sr., Ed., Academic Press, 25-55. 2. NPCC, (2010) “Climate Change Adaptation in New York City: Building a Risk Management Response” New York City Panel on Climate Change 2009 Report. Vol. 1196C. Rosenzweig and W. Solecki, Eds. Wiley-Blackwell, 328 pp.

1 Comment

It Took Some Convincing...Bruce and Nancy Rivington moved their entire farm and family of six from Ontario, Canada to Hamilton, NY in order to give their cows more chances to graze. But, just as Red Gate Farm wasn’t always a grazing farm , Bruce and Nancy were not always graziers. “I kind of made fun of it, [grazing]” Bruce explains, “It seemed stupid, why’d you want to do that when you could just… get more milk production by bringing the feed to the cows?” In Canada, the Rivingtons were content with growing, cultivating, and harvesting crops for the purpose of feeding to their herd. They had a plenty high milk production per cow. Why would they want to give up something they were good at? It wasn’t until they attended a talk by Sonny Golden, a grazing and nutrition specialist from Springfield, PA, that the Rivingtons began to examine their management choices. “He says, ‘You plant corn. What grows? Grass. You plant soybeans. What grows? Grass. You plant barley. What grows? Grass! Why aren’t you growing grass?!’ Which made a lot of sense.” Bruce reminisced. Bruce and Nancy realized they were producing a large quantity of milk, but the costs of such high production were taking their toll. As Bruce remembers, “We were hauling all the feed to the cows, but we were wearing out ourselves, our cows, the machinery, the barn.” Therefore, the Rivingtons decided to try to work within the naturalized system of pasture and ruminant animals, instead of against it, and began practicing grazing in 1994.

Grazing has more than just financial benefits. It improves the quality of life for the cows. In addition to the health benefits of eating fresh grass, they get to engage with their herd mates and the environment naturally as they enjoy the outdoors. When carefully managed, grazing can improve or maintain environmental health as well, through increasing soil health, biodiversity, and even carbon sequestration.

Most pasture plants have evolved to be grazed, and there are dozens of species of grass, fescue and legumes that a cow can choose from. Grazing actually stimulates these plants' growth. Yet, if grazed too short, pasture plants struggle to capture energy from the sun and must move their stored resources in their roots to grow new leaves. Being grazed too short, or too often, time after time will deplete the plant’s energy reserves, leaving an unproductive pasture, and even plant death. However, depending on the season, weather, and the type of plant, grass will grow at variable speeds. In order to maintain the health of the pasture, so that it remains productive in future seasons, the Rivingtons must pay attention to these changes and adjust their grazing plan accordingly. They may give a section of field a longer time to recover based on how quickly it is regrowing, or put the cows in a larger section so the pressure of grazing is spread thinner over the field. The Positive FeedbackBy keeping up this management, the Rivington family and their farm team maintain a positive feedback loop that builds soil and grows nutrient dense grass for their cows. The Rivingtons also enjoy the benefits of not having to purchase and handle certain petroleum based inputs, such as pesticides, herbicides or fertilizer. Practicing grazing means much more time spent in the fields, retrieving cows for milking, moving fencing, or just watching the grass grow - all of which is pretty good exercise (If you don’t believe us, just try racing Bruce up his favorite pasture hill).

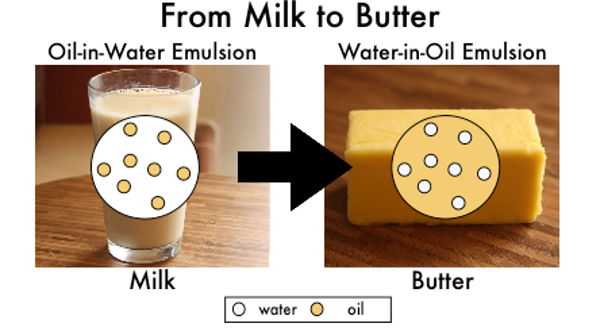

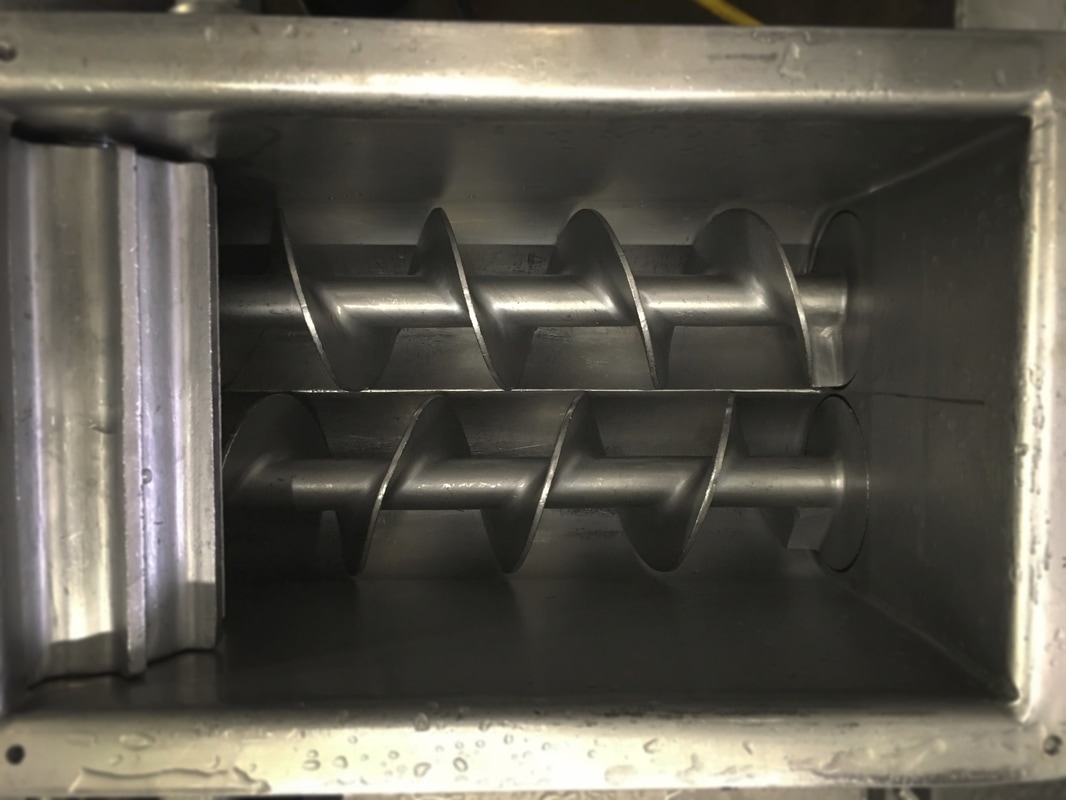

It is true - their cows don’t make as milk as they used to on grain, but the Rivingtons have found a system that is attuned with their values and gives them a lifestyle that suits their family, their farm team, their pastures, their cows, and you, our customers. Don’t just take our word for it, visit the farm on Madison County’s Open Farm Day to experience the joy of a grazing dairy yourself. We’ll have tours, activities, and, of course, plenty of Meadow Butter. This June, we are inviting you, our customers, to join us in celebrating National Dairy Month - an annual tradition that acknowledges the contributions of the dairy industry to our health, our communities, and our environment. Originally created as National Milk Month in 1937 for the purpose of promoting the sale of milk, the National Dairy Council changed the name as the public embraced the opportunity to recognize the significant role that all dairy farmers and processors play in the food system. As a dairy processing business, we would like to celebrate National Dairy Month by highlighting the...well...process of turning local milk into your favorite Meadow Butter and Crème Fraîche. This week we will be shedding light on the details of our Meadow Butter production. Why Butter? When Kriemhild Dairy Farms was established in 2010, we were already committed to the advancement of grazing dairies and the creation of high-quality, grass-grazed dairy food. The flavor and nutritional benefits of grass-grazed dairy products manifest the the best in high-fat products. Therefore, when Kriemhild was developing its first product, butter was a natural choice, and ultimately became our signature creation. Our Co-Packer However, as a start-up agribusiness, we would not have been able to create our Meadow Butter without the unique partnership we have with our co-packer, Queensboro Farm Products in Canastota, NY. At the time of our founding, the farmers who founded Kriemhild -- including co-owners Bruce and Nancy Rivington, owners of Red Gate Farm -- were already shipping their milk to Queensboro. They were aware that Queensboro had a reputation for making butter with a higher than average butterfat, so it was a perfect place to begin our butter production. A typical relationship with a co-packer implies the employees of the facility handle all of the production and packing of a product for an external company. Our relationship with Queensboro, is atypical in that we, as a company, physically take part in the production and packing of our butter within the facility using a combination of both our own and Queensboro’s equipment. Making Dreams Out of Cream Red Gate Farm’s grass-fed milk is picked up and delivered by a trucking service and sold to Queensboro Farm Products every other day. The cream is separated from milk using centrifugal cream separator. This process, which takes about 24 hours naturally, only takes about 13 minutes. The remaining skim milk is sold on the general milk market or used to make other Queensboro products. The cream, which is approximately 38% fat, is pasteurized and transferred to a vat to temper. During the tempering process, between 18 and 24 hours, the fat globule restructures itself and continues to release latent heat. Once the cream has tempered, it’s then piped into a barrel churn. 42,500 pounds of Red Gate Farm’s milk will yield approximately 2,000 pounds of butter, however, this number will vary depending of the percentage of butterfat in the milk. The churn is a mechanical barrel that will spin about the speed of a clothes drying machine, tumbling the cream. The agitation of the cream disturbs the hydrophobic phospholipid membranes surrounding the milkfat globules. As Dr. Robert Bradley likes to describe it in his book, ‘Better Butter’: "Cream is an oil-in-water emulsion that turns into butter when inverted to a water-in-oil emulsion." After about 45 minutes of churning, small clumps start to form, a state known as “popcorn butter” or “butter grains”. At this point the whey is drained, the butter rinsed, drained again and the butter is sold and turned over to Kriemhild. As a team, we don hair nets, plastic aprons, clean rubber boots, and disposable gloves to prepare for a day of packing butter. We begin by doing a complete wash of all our equipment. If we are making salted butter, salt is added to the “popcorn butter” and then it is put through about another five minutes of churning. The fat globules that form the small clumps continue to fuse to each other, pushing our air and moisture, to a point where it is a single creamy, firm mass of butter. We use a mix of technology and elbow grease to pack our butter into different sized containers. All the butter is taken from the churn and placed in a low sheer pump with two strong metal augers that push the butter through a round pipe, similar to a play-doh factory toy. As the butter comes from the pipe it is cut to a certain size, placed on wax paper, and hand rolled to create our traditional rolls. Our two pound, five pound, and 50 pound sizes are also all hand packed. The only size not hand-packed is our 8oz container. To fill our half-pounders, our butter pump is connected to a rotary filler which directly fills our screen printed tubs to an accurate weight, places and heat seals a piece of foil to the top, and presses a lid to close it. When all the butter is packed in containers, it’s then put into labeled boxes for either direct delivery to one of our wholesale accounts or for storage until later. Then, the whole production room and equipment need to be rinsed, washed, and sanitized again. Depending on the size of the batch of butter, and the sizes of units we are packing, a day of butter production can last from 4 to 8 hours. This does not include the time it takes to load the pallets of boxes onto our refrigerated truck, travel back to our headquarters, and then unload and organize our inventory. Food production is also physically intense. It involves standing on hard ground for long hours, tedious periods or repetitive motions, lifting and moving heavy boxes, and no matter how hard we try to not get wet, we always get wet during washing. From Our Hands to Yours Food processing is hard work, but we love to be able to see the creation of our butter from pasture through to market. And although our reach is far, and growing, when you meet one of our team, whether they're delivering your order or at the farmer’s market, you can know that team member handing you your butter is the same person who has taken part in making it. Would grass by any other name be as green? | A New-World Commitment and an Old-World Story3/13/2017 The love story of grazing. From the beginning, our labels on both our Meadow Butter and Crème Fraîche have always read: “From our Grass-Fed Cows.” As we have grown from a small local company to one with a wider regional presence, we have and continue to reflect on our labeling choices to ensure that we are communicating clearly and accurately about our products. Recently, two of Kriemhild’s owners attended the 2017 American Grassfed Association Conference (AGA) at The Stone Barns Center for Food and Agriculture. This conference spoke directly to our commitment to the agricultural practice of grazing, and to its impact on creating a better production ecosystem for our farmers, our farmers’ animals, our customers, and our environment. After attending the AGA conference, we felt inspired to make a finer, yet very important, distinction in our labeling. “Grass-Grazed” and “Grass-Fed” As you, our customer, inquires more about the origins of their food, the need for more exacting label standards have grown. In response to the greenwashing free-for-all that has been occurring through American supermarkets, the AGA presented their new 100% Grass-Fed Dairy Standard. This new 100% Grass-Fed Dairy label is the next critical step towards complete transparency and consistency throughout our food system. We at Kriemhild want to honor that industry growth, which is why we are committing to following these new labeling standards. As part of this commitment, we have begun to transition our Crème Fraîche labeling from “Grass-Fed” (the same as we label our Meadow Butter) to be newly distinguished as “Grass-Grazed.” Although having labeled our Crème Fraîche “Grass-Fed” before was not a technical misnomer for the management style of our Crème Fraîche dairy producers, we feel that “Grass-Grazed” is now a more transparent and consistent descriptor. So, what do we mean by Grass-Grazed? The milk for our Crème Fraîche comes from four small Amish family farms in Chenango County, NY. Their cows’ pasture-based diets are supplemented with a portion of hay, Non-GMO corn silage (a ferment) and/or Non-GMO grain depending on the scale of the family’s farm. All of these Crème Fraîche partner farms’ diet plans are greater than 40% pasture grass, which exceeds the 30% minimum set by the National Organic Standard for pasture intake by grazing. So, when you now see “Grass-Grazed” on Kriemhild Crème Fraîche labels, you know that the cows have a diet that consists of a minimum of 40% fresh pasture during the grazing season, and that their diet was supplemented first with hay, then Non-GMO grain or Non-GMO corn silage. As before and as always, our Meadow Butter remains distinguished as a “Grass-Fed” product from cows on a diet of only pasture, hay, and hay ferment. Our Amish Farm Partners: The Origin of your Crème Fraîche New York has the fastest-growing Amish population of all states, and very often, when Amish families settle in NY they buy and rejuvenate old dairy farms. New York state is the third leading producer of dairy products in the United States, and yet from 1990 to 2010, NY lost half of its smaller dairy farms. This decline of family farms has negatively impacted local economies and degraded the rural character and quality of open spaces in upstate New York. Our Amish farm partners play a critical role in reversing this trend, revitalizing neglected farmland and supporting local economies. Eli Hershberger, one of our Amish farm partners, moved to NY with his family when he was 16 years old. He began dairy farming after his brother passed away from a premature heart attack, leaving behind a wife and eight children. Together, this resilient family farms a small herd of 15 milking cows, which are all milked by hand every day. The milk is carried in traditional milk cans to a shared building that houses four large commercial milk tanks, one for each Amish dairy farm we work with. From there, the milk is picked up and trucked to our co-packer facility in Norwich, NY where it is cultured and packaged into your Crème Fraîche. Environmental stewardship is the cornerstone of Amish agricultural practices. If Eli could increase the share of grazing time he gives his cows, he would. At the time being, land and fencing are his largest challenges. Permanent fencing is a significant expense, and given that many Amish avoid using electricity, cheaper temporary electric wire is not an option. Like many farmers, Eli is working the best he can with the resources he has. He is aware that if he supplements too little grain the cows will overgraze the finite pasture he has for them, which causes lasting detrimental effects to the land. In order to assure that his land will be able to produce enough fresh grass throughout the grazing season, Eli gives supplemental non-GMO feed to manage the ecological pressure on his fields. Kriemhild owners, Bruce and Lindsey, inspecting Eli's farm & equipment. Our Commitment

Eli and our other Amish family farms have always produced high quality milk with an ecological and health-centered conscience. We know they will continue to seek excellence in environmental stewardship and animal husbandry, and now you know we just have a better name for their practices: "Grass-Grazed" Dairy. We feel this distinction offers you greater transparency and also consistency with regards to labeling. Our commitment to you to provide ecological, nutritional, and ethical excellence is only stronger with our newly defined terminology, as is our commitment to our local communities and the family farms we partner with. The Subtle Queen of Cultured DairyThis week, we thought we’d let you in on some of the behind-the-scenes action of our crème fraîche breakfast challenge. Many of the recipes we’ve compiled originally had yogurt as the main dairy ingredient, and we took the liberty of switching that out for our own crème fraîche. Since we had several recipes in our 30—day challenge that happened to be smoothies, we wanted to know just how well our crème fraîche variations performed versus ones made with plain yogurt. First, let’s lay out the difference between yogurt and crème fraîche... Especially since distinctions between cultured dairy foods are subtle, compared to the more obvious lines between items like liquid milk and solid cheese:

Now that we know the nitty gritty, let’s see how crème fraîche and yogurt compete as the main component of a delicious dairy smoothie. Using the mixed berry with lemongrass smoothie, our home cook and team member, Heidi, blended up both a yogurt and crème fraîche version. Can you guess which uses our Crème Fraîche? If you guessed the left, you’re right. Considering crème fraîche is born from heavy cream, it’s not too shocking that it affects the color of the smoothie much like cream would affect coffee. But, how much creamier is it than the yogurt smoothie? We had to know. So, we spilled it. Literally. Although, visually, both smoothies seem — for lack of a better word — smooth, the crème fraîche version proved its top-notch creaminess with superior viscosity, pouring out of the glass in a single, connected stream while the yogurt smoothie was prone to slushy clumps and disconnected droplets. To your palate, the crème fraîche version definitely presents with a thicker, richer body. So, what does this mean for your breakfast? Of course personal preferences come into play, but if you yearn for a richer, creamier smoothie with gut-healthy probiotics, crème fraîche is the best dairy ingredient for your smoothy. Also, let’s not forget that morning is a better time to consume higher-fat foods (with a clean conscience) for sustained energy throughout the rest of the day. This one-two punch of flavor and fullness makes crème fraîche smoothies a healthy knockout for your next grab-and-go breakfast! First of all, let's call it Full-Fat Dairy...There’s no hiding that at Kriemhild we’re focused on fat. It’s hard to find a more nutritionally disputed food than full-fat dairy, and we’re at the extreme end of the opinion spectrum by making a butter with higher-than-average butterfat percentage (on purpose, no less!), and now by making crème fraîche, which has higher fat content than either yogurt or sour cream.

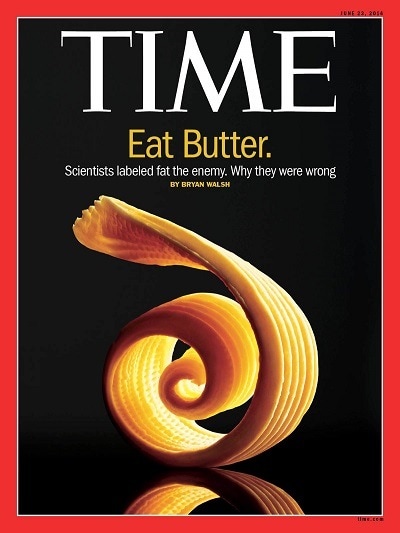

It’s not uncommon for us to be playfully scolded by customers for selling such good-tasting full-fat dairy products; a “tempting dietary sin,” they say. And we understand, conventional dietary advice has been to avoid saturated fat to reduce the risk of heart disease and maintain an overall healthy diet. However, over the past 7 years there’s been growing scientific evidence to challenge the findings that inspired the original USDA Food Pyramid in 1992 (1,2). What we’re really trying to say it this: we’re not out to get you, and neither is fat. We truly believe we are providing you with quality dairy that has authentic nutritional benefits. We agree with the scientific proof that saturated fats in our dairy products are not inherently bad, and are actually an important part of a healthy diet. In response to the growing scientific consensus pardoning saturated fats, Americans are increasingly switching to full-fat foods from low-fat options. A report published by the Credit Suisse Research Institute shows that butter and whole milk sales are rising. In 2014, butter sales rose 14% and in the first half of 2015 whole milk sale increase 11% while sales of skim milk dropped 14% (3). Being that fats, particularly saturated fats, have been the scapegoats of the nutritional world for decades, their vital roles in our bodies have been greatly unappreciated and misunderstood:

Of the three macronutrients —Protein, Carbohydrates and Fat— Fat is the most efficiently absorbed by our bodies for our energy needs. It’s that last little tidbit of information that inspired our 30 days of crème fraîche for breakfast challenge. Who hasn’t suffered through a low-fat breakfast only to be hungry an hour later? Fats signal satiety to our brains and slow down nutrient absorption so you eat less and feel full longer. Adding crème fraîche is one way to make an interesting breakfast that carries you over until lunch. Our fat advocacy is born from our advocacy of food from grass-fed animals. It’s, in truth, the fat of these foods that carry the benefits of the animals’ grass-fed diets. The fat profile of milk and other dairy products depends on what the cows eat. Grass-fed dairy contain more omega-3 fatty acids. Milk from cows with grass-based diets contains between 2.5 and 5 times the levels of omega-3 of the milk of grain-fed cows and present a better omega-6 to omega-3 ratio. Grass-fed milk can contain 1.5 to 2.5 times higher levels of conjugated linoleum acid (CLA), which helps reduce insulin sensitivity and lessen symptoms of inflammatory disorders (4). Omega-3 isn’t just a salmon thing (although salmon and crème fraîche go great together, not going to lie). So, if you’ve ever wondered why we shamelessly announce the full-fat content of our dairy, this is why. We’re convinced that full fat deserves a chance. Are you? Check out Today's recipe for Day 7 of the 30-Days of Crème Fraîche for Breakfast challenge. Cited Sources:

|

As the Butter Churns

Author: Ellen Fagan and Victoria PeilaCategories

All

Archives

November 2019

|

Where our HEart is

|

FOLLOW US |

what our customers are saying"Thank you! Even though I'm 5 hours away...I can't live without you. Got my shipment today.

#kriemhildbutterlove" -- Jennifer in Mystic, Connecticut |

Copyright 2020 © Kriemhild Dairy Farms, LLC

RSS Feed

RSS Feed