|

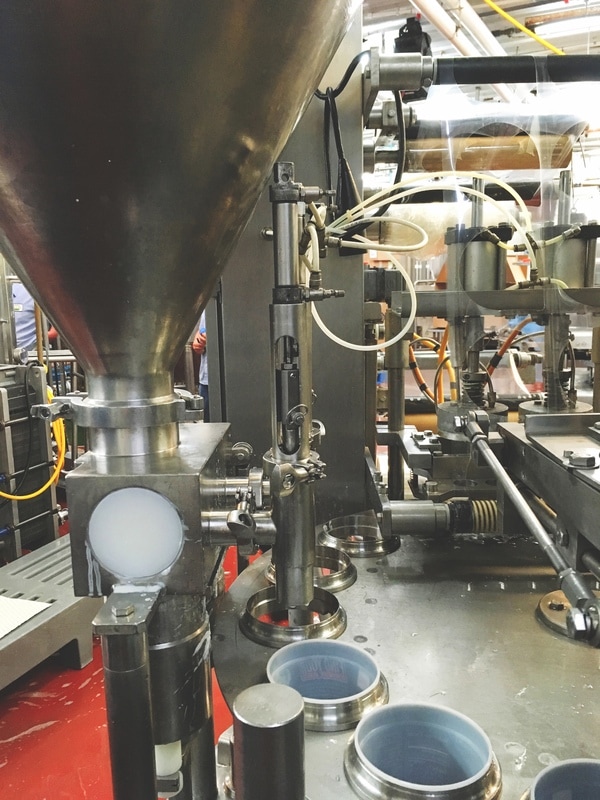

Taking The Next Step When we became ready to expand the Kriemhild brand and develop another product we searched our stomachs for something unique but also something that echoed the qualities of our butter: high butterfat percentage, full fat, and grass-grazed. We settled on crème fraîche, our cultured heavy cream. To turn this dream into cultured cream, we needed the help of our second dairy co-packer: Sunrise Family Farms in Norwich, NY. Opened for business in 1999 by Dave and Susan Evans, Sunrise Family Farms collects milk from multiple dairy farms, organic and conventional, in the surrounding Chenango County area, processes, and packages it for over 10 different private dairy labels. Sunrise Family Farms is neither a large manufacturer, nor a tiny one. This mid-size operation makes it possible for them to serve national brands, and at the same time package for smaller local brands (like us!) allowing them to grow their production and diversify their product line. The creamery currently runs multiple shifts, 24 hours a day, and employs a team of more than 50 dedicated workers. Being familiar with their high-quality yogurts, and with their availability of local, grass-grazed cream, Sunrise Family Farms was our go-to for co-packing our crème fraîche. Getting Cultured The process for making crème fraîche is similar to making yogurt or sour cream, but even more simple. When the milk arrives to sunrise family farms, it is pasteurized at a high temperature, 161 degrees fahrenheit, for a short amount of time, 15 seconds. This technique, known as high temperature short time (HTST), is the most common method of pasteurization in the dairy industry. (It is a separate method from Ultra pasteurization (UHT), which holds milk at 280 degrees fahrenheit for 2 seconds or vat pasteurization which holds milk at 145 degrees for 30 minutes) After pasteurization, milk intended for crème fraîche production is held at 80 degrees fahrenheit. The cream is separated using a centrifugal cream separator, and the remaining skim milk is used to produce other products within the facility. The cream is moved to a vat, and a mix of cultures is added. The mix of cultures is different from yogurt. The main cultures in yogurt, Lactobacillus bulgaricus and Streptococcus thermophilus, are heat loving bacteria. Therefore, when making yogurt, the milk is fermented between 110 and 115 degrees fahrenheit. The cultures in crème fraîche include L. cremoris, L. lactis, and L. biovar diacetylactis, and often others. When these bacteria are added to cream, they consume the lactose, the sugar found in milk, and convert it into energy leaving lactic acid as a byproduct. The lactic acid decreases the pH of the cream, making it inhospitable to other competing bacteria that encourage spoilage, and changing the flavor. It is L. biovar diacetylactis, specifically, that produces the buttery flavor you know to be distinctive of crème fraîche. After the culture is added, the cultured cream is sent through a pipe into a rotary filler that fills and encloses individual tubs. As the units come off the filler they are brought to a well ventilated incubating room that is held at 80 degrees fahrenheit as the cream “sets”. As the pH decrease due to the increased production of lactic acid by the live bacteria, proteins in the cream begin to unfold. This process thickens the cream as it incubates from 12 to 18 hours before it is packaged, refrigerated, and then picked up by Kriemhild. Co-packers are essential to the dairy industry Even though you might buy a national brand, local co-packers can make it possible that the milk in your food is sourced from local farmers. For smaller businesses, like us, co-packers can be a significant stepping stone on the way to their own processing facility. Sunrise Family Farms, in particular, serves as an important outlet for a dairy rich region and provides jobs in an otherwise economically struggling area. As a fellow small business, we are proud to have Sunrise Family Farms as our co-packer. We both strive to support family dairies in our community.

1 Comment

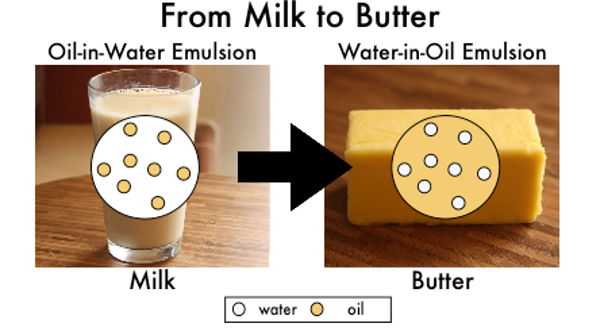

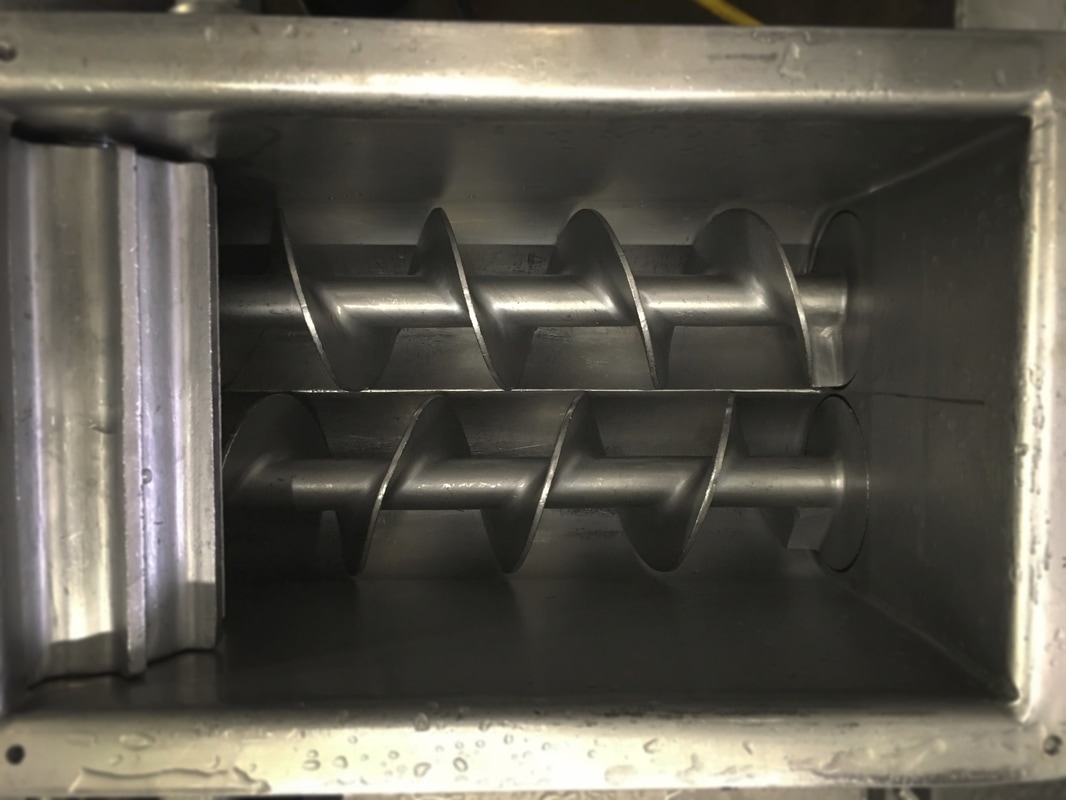

This June, we are inviting you, our customers, to join us in celebrating National Dairy Month - an annual tradition that acknowledges the contributions of the dairy industry to our health, our communities, and our environment. Originally created as National Milk Month in 1937 for the purpose of promoting the sale of milk, the National Dairy Council changed the name as the public embraced the opportunity to recognize the significant role that all dairy farmers and processors play in the food system. As a dairy processing business, we would like to celebrate National Dairy Month by highlighting the...well...process of turning local milk into your favorite Meadow Butter and Crème Fraîche. This week we will be shedding light on the details of our Meadow Butter production. Why Butter? When Kriemhild Dairy Farms was established in 2010, we were already committed to the advancement of grazing dairies and the creation of high-quality, grass-grazed dairy food. The flavor and nutritional benefits of grass-grazed dairy products manifest the the best in high-fat products. Therefore, when Kriemhild was developing its first product, butter was a natural choice, and ultimately became our signature creation. Our Co-Packer However, as a start-up agribusiness, we would not have been able to create our Meadow Butter without the unique partnership we have with our co-packer, Queensboro Farm Products in Canastota, NY. At the time of our founding, the farmers who founded Kriemhild -- including co-owners Bruce and Nancy Rivington, owners of Red Gate Farm -- were already shipping their milk to Queensboro. They were aware that Queensboro had a reputation for making butter with a higher than average butterfat, so it was a perfect place to begin our butter production. A typical relationship with a co-packer implies the employees of the facility handle all of the production and packing of a product for an external company. Our relationship with Queensboro, is atypical in that we, as a company, physically take part in the production and packing of our butter within the facility using a combination of both our own and Queensboro’s equipment. Making Dreams Out of Cream Red Gate Farm’s grass-fed milk is picked up and delivered by a trucking service and sold to Queensboro Farm Products every other day. The cream is separated from milk using centrifugal cream separator. This process, which takes about 24 hours naturally, only takes about 13 minutes. The remaining skim milk is sold on the general milk market or used to make other Queensboro products. The cream, which is approximately 38% fat, is pasteurized and transferred to a vat to temper. During the tempering process, between 18 and 24 hours, the fat globule restructures itself and continues to release latent heat. Once the cream has tempered, it’s then piped into a barrel churn. 42,500 pounds of Red Gate Farm’s milk will yield approximately 2,000 pounds of butter, however, this number will vary depending of the percentage of butterfat in the milk. The churn is a mechanical barrel that will spin about the speed of a clothes drying machine, tumbling the cream. The agitation of the cream disturbs the hydrophobic phospholipid membranes surrounding the milkfat globules. As Dr. Robert Bradley likes to describe it in his book, ‘Better Butter’: "Cream is an oil-in-water emulsion that turns into butter when inverted to a water-in-oil emulsion." After about 45 minutes of churning, small clumps start to form, a state known as “popcorn butter” or “butter grains”. At this point the whey is drained, the butter rinsed, drained again and the butter is sold and turned over to Kriemhild. As a team, we don hair nets, plastic aprons, clean rubber boots, and disposable gloves to prepare for a day of packing butter. We begin by doing a complete wash of all our equipment. If we are making salted butter, salt is added to the “popcorn butter” and then it is put through about another five minutes of churning. The fat globules that form the small clumps continue to fuse to each other, pushing our air and moisture, to a point where it is a single creamy, firm mass of butter. We use a mix of technology and elbow grease to pack our butter into different sized containers. All the butter is taken from the churn and placed in a low sheer pump with two strong metal augers that push the butter through a round pipe, similar to a play-doh factory toy. As the butter comes from the pipe it is cut to a certain size, placed on wax paper, and hand rolled to create our traditional rolls. Our two pound, five pound, and 50 pound sizes are also all hand packed. The only size not hand-packed is our 8oz container. To fill our half-pounders, our butter pump is connected to a rotary filler which directly fills our screen printed tubs to an accurate weight, places and heat seals a piece of foil to the top, and presses a lid to close it. When all the butter is packed in containers, it’s then put into labeled boxes for either direct delivery to one of our wholesale accounts or for storage until later. Then, the whole production room and equipment need to be rinsed, washed, and sanitized again. Depending on the size of the batch of butter, and the sizes of units we are packing, a day of butter production can last from 4 to 8 hours. This does not include the time it takes to load the pallets of boxes onto our refrigerated truck, travel back to our headquarters, and then unload and organize our inventory. Food production is also physically intense. It involves standing on hard ground for long hours, tedious periods or repetitive motions, lifting and moving heavy boxes, and no matter how hard we try to not get wet, we always get wet during washing. From Our Hands to Yours Food processing is hard work, but we love to be able to see the creation of our butter from pasture through to market. And although our reach is far, and growing, when you meet one of our team, whether they're delivering your order or at the farmer’s market, you can know that team member handing you your butter is the same person who has taken part in making it. |

As the Butter Churns

Author: Ellen Fagan and Victoria PeilaCategories

All

Archives

November 2019

|

Where our HEart is

|

FOLLOW US |

what our customers are saying"Thank you! Even though I'm 5 hours away...I can't live without you. Got my shipment today.

#kriemhildbutterlove" -- Jennifer in Mystic, Connecticut |

Copyright 2020 © Kriemhild Dairy Farms, LLC

RSS Feed

RSS Feed