|

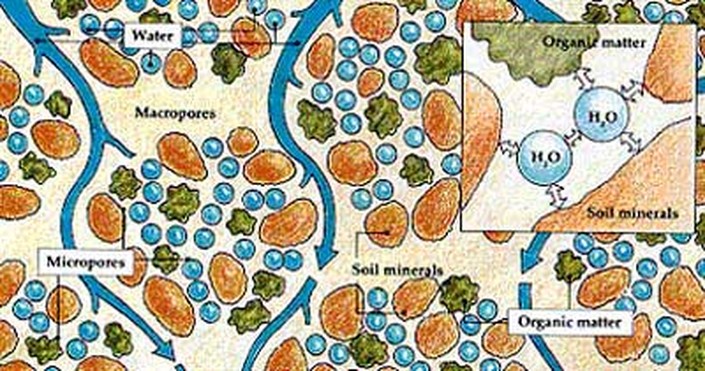

This year, it seems to be that “April Showers” turned into May showers. And then June Showers. Now its July and the northeast still seems to be getting drenched at least twice a week. The constant thunderstorms and heavy rainfall is not just an inconvenience, but a danger as flash floods have become an occurrence around New York State. Even after the rainfall, the resulting influx of water is washing over roads, causing power outages, and even damaging homes. Farms struggle with heavy rainfall and flooding as well. Wet conditions force farmers to keep their heavy tractors out of the field to avoid getting stuck. Standing water from saturated soils or flooding can drown crops and pasture plants, both posing significant losses. Bruce and Nancy Rivington, Kriemhild co-owners and farmers of Red Gate Farm, own about 700 acres of contiguous land. Despite the inundation of precipitation since spring, none of their pastures had flooded this year. Now, this may be due to luck, but it is likely due to the impact grazing has on their soils. Climate Change is HereWe’ve discussed how the practice of grazing encourages carbon sequestration, but this is not the only way that grazing combats climate change. The Northeast United States has had a 70% increase in the amount of heavy precipitation events between the late 1950s and 2010, and winter and spring precipitation is predicted to only increase (1) . On the other side, as temperatures in the summer and fall increase, seasonal drought is projected to become more frequent (2). With these climate predictions, a farmer’s best choice is to cultivate a resilient soil that can handle both drought as well as heavy precipitation. The best way to insulate soils from the impacts of extreme wet or dry conditions is to develop a strong soil structure. Most are familiar with the importance of nutrients and minerals in soil, but without a structure in which water and air can move, plants have difficulty pushing their roots through the soil and accessing those nutrients. The structure of the soil is how the particles are held together, or aggregated. Grass naturally does a nice job of holding soils together with its fine root system and, if managed correctly, it also covers the soil and protects it from erosion. The Tiniest LivestockAs pasture plants photosynthesize, they create nutrients of their own that they excrete into the soil as exudate. Millions of microorganisms and mycorrhizal fungi, feed upon this exudate, a symbiotic relationship, and in turn bring nutrients to the plant. While this abundance of micro-life feeds on their exudate buffet, excrete waste, and eventually die, they create organic matter and other glue-like protein substances that hold soil particles together. This structure building allows micro and macro pores to manifest in the soil, making highways for air and water to travel to plants roots, micro critters and slightly larger soil inhabitants, such as worms, dung beetles, grubs and moles. A well-aggregated soil is made up of half pore spaces and half solid particles.

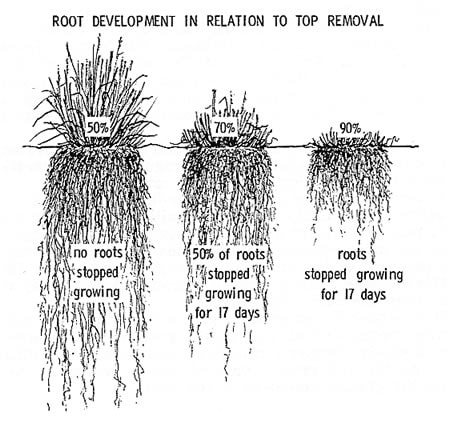

Bruce and Nancy’s grazing management is centered on soil health. Red Gate Farm’s perennial pastures’ roots run deep. The cows are allowed to graze each paddock down to a certain height, but then are rotated to a new field to give the grazed pasture plants time to rebound. When plants are grazed, they slough off a portion of their roots. These roots decompose and add to the soils organic matter. While the pasture rests, the plants regrow and their roots penetrate deeper into the soil, making passageways for air and water to reach to lower soil layers and while accessing nutrients stored in the depths. All along the way, microorganisms interact with the expanding root systems, creating more organic matter and “soil glue”, building a resilient soil structure that acts like a sponge. This system keeps Red Gate Farm dry when it rains, and green when it’s dry. It’s easy to get caught up in the individual health benefits of grass-fed and grass-grazed products and overlook the overarching natural cycles that responsible grass-based production perpetuates. It’s important to us to remember that our Meadow Butter is the result of a complex, thriving ecosystem - and we plan to keep it that way. So, join us at the Red Gate Farm on Open Farm Day as we dig deeper into how the Rivingtons’ cows turn pasture into your favorite Meadow Butter on July 29th. Cited Sources:

1. Groisman, P. Y., R. W. Knight, and O. G. Zolina, (2013) “Recent trends in regional and global intense precipitation patterns.” Climate Vulnerability, R.A. Pielke, Sr., Ed., Academic Press, 25-55. 2. NPCC, (2010) “Climate Change Adaptation in New York City: Building a Risk Management Response” New York City Panel on Climate Change 2009 Report. Vol. 1196C. Rosenzweig and W. Solecki, Eds. Wiley-Blackwell, 328 pp.

1 Comment

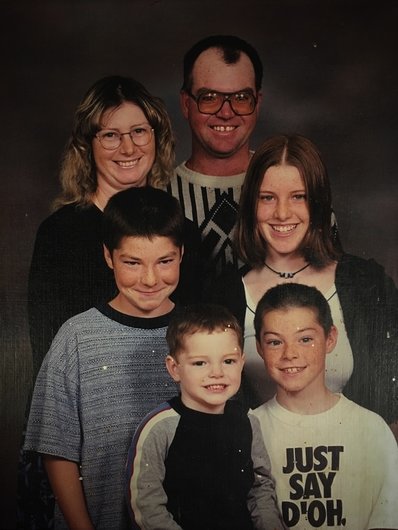

It Took Some Convincing...Bruce and Nancy Rivington moved their entire farm and family of six from Ontario, Canada to Hamilton, NY in order to give their cows more chances to graze. But, just as Red Gate Farm wasn’t always a grazing farm , Bruce and Nancy were not always graziers. “I kind of made fun of it, [grazing]” Bruce explains, “It seemed stupid, why’d you want to do that when you could just… get more milk production by bringing the feed to the cows?” In Canada, the Rivingtons were content with growing, cultivating, and harvesting crops for the purpose of feeding to their herd. They had a plenty high milk production per cow. Why would they want to give up something they were good at? It wasn’t until they attended a talk by Sonny Golden, a grazing and nutrition specialist from Springfield, PA, that the Rivingtons began to examine their management choices. “He says, ‘You plant corn. What grows? Grass. You plant soybeans. What grows? Grass. You plant barley. What grows? Grass! Why aren’t you growing grass?!’ Which made a lot of sense.” Bruce reminisced. Bruce and Nancy realized they were producing a large quantity of milk, but the costs of such high production were taking their toll. As Bruce remembers, “We were hauling all the feed to the cows, but we were wearing out ourselves, our cows, the machinery, the barn.” Therefore, the Rivingtons decided to try to work within the naturalized system of pasture and ruminant animals, instead of against it, and began practicing grazing in 1994.

Grazing has more than just financial benefits. It improves the quality of life for the cows. In addition to the health benefits of eating fresh grass, they get to engage with their herd mates and the environment naturally as they enjoy the outdoors. When carefully managed, grazing can improve or maintain environmental health as well, through increasing soil health, biodiversity, and even carbon sequestration.

Most pasture plants have evolved to be grazed, and there are dozens of species of grass, fescue and legumes that a cow can choose from. Grazing actually stimulates these plants' growth. Yet, if grazed too short, pasture plants struggle to capture energy from the sun and must move their stored resources in their roots to grow new leaves. Being grazed too short, or too often, time after time will deplete the plant’s energy reserves, leaving an unproductive pasture, and even plant death. However, depending on the season, weather, and the type of plant, grass will grow at variable speeds. In order to maintain the health of the pasture, so that it remains productive in future seasons, the Rivingtons must pay attention to these changes and adjust their grazing plan accordingly. They may give a section of field a longer time to recover based on how quickly it is regrowing, or put the cows in a larger section so the pressure of grazing is spread thinner over the field. The Positive FeedbackBy keeping up this management, the Rivington family and their farm team maintain a positive feedback loop that builds soil and grows nutrient dense grass for their cows. The Rivingtons also enjoy the benefits of not having to purchase and handle certain petroleum based inputs, such as pesticides, herbicides or fertilizer. Practicing grazing means much more time spent in the fields, retrieving cows for milking, moving fencing, or just watching the grass grow - all of which is pretty good exercise (If you don’t believe us, just try racing Bruce up his favorite pasture hill).

It is true - their cows don’t make as milk as they used to on grain, but the Rivingtons have found a system that is attuned with their values and gives them a lifestyle that suits their family, their farm team, their pastures, their cows, and you, our customers. Don’t just take our word for it, visit the farm on Madison County’s Open Farm Day to experience the joy of a grazing dairy yourself. We’ll have tours, activities, and, of course, plenty of Meadow Butter. Ingredients:

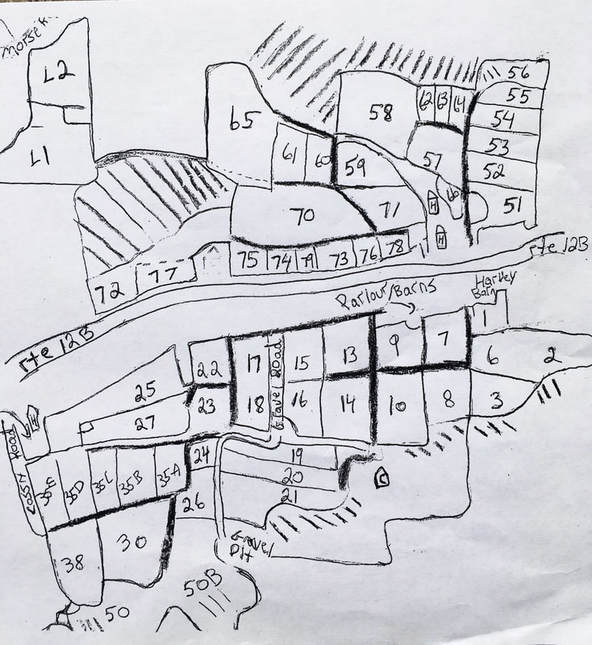

Instructions: Combine vegetable oil, thyme, and Dijon mustard in a large bowl and mix together. Season the meat with salt and pepper and toss in the marinade, cover and refrigerate 4 hours or overnight. Remove the meat from the marinade. Reserve the marinade. Heat 1 tablespoon butter in large, deep-sided sauté pan over medium heat. Add the scallions and garlic. Season with salt and pepper and cook until tender, about 5 minutes. Remove from the pan. Add a tablespoon of butter, and brown the meat pieces on both sides, about 2 minutes per side. Deglaze the pan with the champagne vinegar. Add the chicken stock and the residual marinade in the bowl. Cover with a piece of parchment paper and then a lid. Cook over the lowest heat , about 20 minutes. Flip the meat over. Cover with parchment and lid and continue cooking 10 minutes. Add the scallions. Then cook until the meat is done, about 20 minutes. Remove the meat from the pan and cover to keep warm. Reduce the sauce until it coats the back of a spoon. Stir in half the tarragon and creme fraîche. If the sauce seems too watery, put the pan back on the heat and reduce it until it is thick. While the sauce is reducing, heat the remaining tablespoon of butter in a small sauté pan over medium heat. Add the radishes and brown all over. Season with salt and pepper. Add the radish leaves, toss and then add the peas, honey, the remaining teaspoons of vinegar and remaining tarragon and toss to coat. Recipe adapted from hegarumfactory.net If you haven’t learned by now, Kriemhild Dairy is intimately connected with Red Gate Farm, our sole seasonal Meadow Butter supplier. Farmers Bruce and Nancy Rivington own 90% of Kriemhild and have had an essential role in developing our values and guiding the direction of our small agricultural business. In fact, we all would consider being able to access and experience the farm a job perk: we get to interact with their beautiful, and curious, herd of cows, have walking privileges to the rolling pastures, and occasionally get roped into doing some farm work. You, or someone you know, might even be familiar with the farm. Kriemhild and Red Gate Farm often collaborate on farm events to encourage people to engage with the staff and animals who contribute to the production of their food. Red Gate hosted its first Calving Day this year, but many visitors’ first experience of the Farm is during Madison County’s Open Farm Day. Red Gate Farm has been participating in Open Farm Day for the 8 years the event has existed, this year will be no different. But, likely unbeknownst to visitors, 17 years ago, Red Gate’s rolling green pastures looked very different than they do today. From Canada to CNYWhen the Rivington Family moved from their dairy farm in Ontario, Canada to New York, they were on a clear-cut mission: to graze. The Rivingtons wanted to increase the amount their cows could graze, and ultimately switch to seasonal dairying for human and herd wellbeing. Although the Canadian supply management policies promised consistent revenue for Canadian dairy farmers, the system would not accept the variable amount of milk produced by a grazing seasonal dairy. With aspirations of expanding their farm and embracing seasonal grazing, the Rivingtons began to search the Empire State for their new home. Nancy and Bruce visited about 18 different farms hoping to find one that was suited for grazing. Mainly, they were searching for at least 400 acres of contiguous land so as to make it possible to move a herd easily from one pasture to the next. This was more of a challenge than expected. “Real estate agents have real funny definitions of contiguous,” Bruce recalls. It was in the depths of winter when the Rivingtons were introduced to Red Gate Farm. Although the land was buried in snow, the Rivingtons knew it was the farm they were looking for. They bought the farm in 2000. Red Gate Farm was a dairy farm historically, but most of its 512 acres had been in conventionally managed corn and alfalfa crops for almost 3 decades. Although rotating corn and alfalfa crops is an effective practice for those who strive to grow an abundance of those two crops, this type of management can take its toll on the land. Bringing Back The Grass Growing a single or limited amount of crops on the same land quickly depleted the soil of its fertility, making it necessary to apply chemical fertilizers to just as quickly supply the exact amount of nutrients the crop needed. Repeated tilling and cultivating also deteriorated the soil. This practice released soil nutrients into the air and broke up the roots and aggregates that held the soil together, increasing the rate of erosion. Bruce remembers discovering the poor condition of the soils, “When we first bought the farm we had to hunt to find an earthworm.”

Despite its sorry condition, Bruce and Nancy knew the healing effect that grazing could have. So, the Rivingtons gave the Red Gate Farm fields their last tilling ever, only to plant an abundance of perennial grass seeds. Starting with a small herd, they gently grazed and mowed the grass to encourage root growth and carbon sequestration. After 5 years of careful and nurturing management, Red Gate Farm began to resemble the farm we all know today: 737 acres of lush green grass carpeting miles of land speckled with colorful moseying cows grazing at their leisure. Even the section of field burned with pesticides was regenerated, and now is ironically one of their most productive pasture, growing almost exclusively native grasses. “That’s the pasture I like to take people up to, to show them,” Bruce boasts. Land that Doesn't Just Work, But LivesThe Rivingtons did not merely transition Red Gate Farm from one crop to another. They reclaimed land stripped of its nutrients, only able to grow corn and alfalfa, and regenerated it into a thriving ecosystem. Their land not only grows nutrient dense grasses, but it also feeds an expansive community of soil microbacteria and microfauna, acts as a habitat for wildlife, and even mitigates greenhouse grasses.

Although this happened long before Kriemhild was established, we would not exist without Red Gate Farm, so we embrace it as part of our story. We hope to help other farmers tell their own similar stories as we grow. Until then, you can visit Red Gate Farm on July 29th as we celebrate Madison County’s Open Farm Day. It’ll be a great chance to learn more about how agriculture can be a pivotal point of community, nutritional, and environmental health. |

As the Butter Churns

Author: Ellen Fagan and Victoria PeilaCategories

All

Archives

November 2019

|

Where our HEart is

|

FOLLOW US |

what our customers are saying"Thank you! Even though I'm 5 hours away...I can't live without you. Got my shipment today.

#kriemhildbutterlove" -- Jennifer in Mystic, Connecticut |

Copyright 2020 © Kriemhild Dairy Farms, LLC

RSS Feed

RSS Feed