|

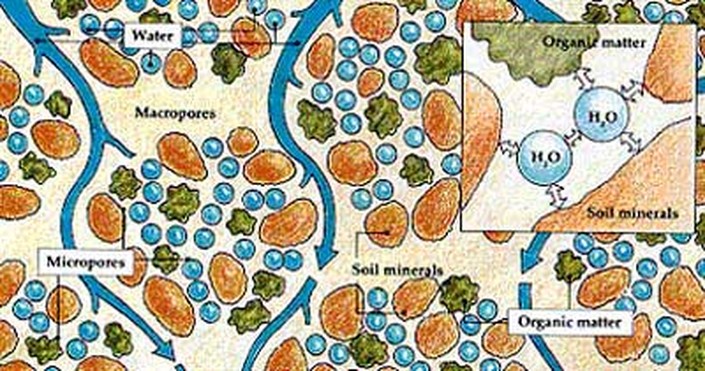

This year, it seems to be that “April Showers” turned into May showers. And then June Showers. Now its July and the northeast still seems to be getting drenched at least twice a week. The constant thunderstorms and heavy rainfall is not just an inconvenience, but a danger as flash floods have become an occurrence around New York State. Even after the rainfall, the resulting influx of water is washing over roads, causing power outages, and even damaging homes. Farms struggle with heavy rainfall and flooding as well. Wet conditions force farmers to keep their heavy tractors out of the field to avoid getting stuck. Standing water from saturated soils or flooding can drown crops and pasture plants, both posing significant losses. Bruce and Nancy Rivington, Kriemhild co-owners and farmers of Red Gate Farm, own about 700 acres of contiguous land. Despite the inundation of precipitation since spring, none of their pastures had flooded this year. Now, this may be due to luck, but it is likely due to the impact grazing has on their soils. Climate Change is HereWe’ve discussed how the practice of grazing encourages carbon sequestration, but this is not the only way that grazing combats climate change. The Northeast United States has had a 70% increase in the amount of heavy precipitation events between the late 1950s and 2010, and winter and spring precipitation is predicted to only increase (1) . On the other side, as temperatures in the summer and fall increase, seasonal drought is projected to become more frequent (2). With these climate predictions, a farmer’s best choice is to cultivate a resilient soil that can handle both drought as well as heavy precipitation. The best way to insulate soils from the impacts of extreme wet or dry conditions is to develop a strong soil structure. Most are familiar with the importance of nutrients and minerals in soil, but without a structure in which water and air can move, plants have difficulty pushing their roots through the soil and accessing those nutrients. The structure of the soil is how the particles are held together, or aggregated. Grass naturally does a nice job of holding soils together with its fine root system and, if managed correctly, it also covers the soil and protects it from erosion. The Tiniest LivestockAs pasture plants photosynthesize, they create nutrients of their own that they excrete into the soil as exudate. Millions of microorganisms and mycorrhizal fungi, feed upon this exudate, a symbiotic relationship, and in turn bring nutrients to the plant. While this abundance of micro-life feeds on their exudate buffet, excrete waste, and eventually die, they create organic matter and other glue-like protein substances that hold soil particles together. This structure building allows micro and macro pores to manifest in the soil, making highways for air and water to travel to plants roots, micro critters and slightly larger soil inhabitants, such as worms, dung beetles, grubs and moles. A well-aggregated soil is made up of half pore spaces and half solid particles.

Bruce and Nancy’s grazing management is centered on soil health. Red Gate Farm’s perennial pastures’ roots run deep. The cows are allowed to graze each paddock down to a certain height, but then are rotated to a new field to give the grazed pasture plants time to rebound. When plants are grazed, they slough off a portion of their roots. These roots decompose and add to the soils organic matter. While the pasture rests, the plants regrow and their roots penetrate deeper into the soil, making passageways for air and water to reach to lower soil layers and while accessing nutrients stored in the depths. All along the way, microorganisms interact with the expanding root systems, creating more organic matter and “soil glue”, building a resilient soil structure that acts like a sponge. This system keeps Red Gate Farm dry when it rains, and green when it’s dry. It’s easy to get caught up in the individual health benefits of grass-fed and grass-grazed products and overlook the overarching natural cycles that responsible grass-based production perpetuates. It’s important to us to remember that our Meadow Butter is the result of a complex, thriving ecosystem - and we plan to keep it that way. So, join us at the Red Gate Farm on Open Farm Day as we dig deeper into how the Rivingtons’ cows turn pasture into your favorite Meadow Butter on July 29th. Cited Sources:

1. Groisman, P. Y., R. W. Knight, and O. G. Zolina, (2013) “Recent trends in regional and global intense precipitation patterns.” Climate Vulnerability, R.A. Pielke, Sr., Ed., Academic Press, 25-55. 2. NPCC, (2010) “Climate Change Adaptation in New York City: Building a Risk Management Response” New York City Panel on Climate Change 2009 Report. Vol. 1196C. Rosenzweig and W. Solecki, Eds. Wiley-Blackwell, 328 pp.

1 Comment

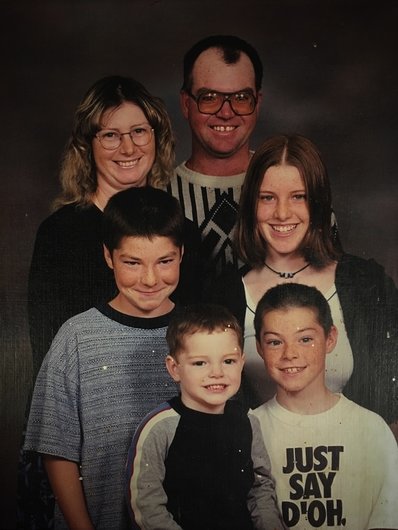

It Took Some Convincing...Bruce and Nancy Rivington moved their entire farm and family of six from Ontario, Canada to Hamilton, NY in order to give their cows more chances to graze. But, just as Red Gate Farm wasn’t always a grazing farm , Bruce and Nancy were not always graziers. “I kind of made fun of it, [grazing]” Bruce explains, “It seemed stupid, why’d you want to do that when you could just… get more milk production by bringing the feed to the cows?” In Canada, the Rivingtons were content with growing, cultivating, and harvesting crops for the purpose of feeding to their herd. They had a plenty high milk production per cow. Why would they want to give up something they were good at? It wasn’t until they attended a talk by Sonny Golden, a grazing and nutrition specialist from Springfield, PA, that the Rivingtons began to examine their management choices. “He says, ‘You plant corn. What grows? Grass. You plant soybeans. What grows? Grass. You plant barley. What grows? Grass! Why aren’t you growing grass?!’ Which made a lot of sense.” Bruce reminisced. Bruce and Nancy realized they were producing a large quantity of milk, but the costs of such high production were taking their toll. As Bruce remembers, “We were hauling all the feed to the cows, but we were wearing out ourselves, our cows, the machinery, the barn.” Therefore, the Rivingtons decided to try to work within the naturalized system of pasture and ruminant animals, instead of against it, and began practicing grazing in 1994.

Grazing has more than just financial benefits. It improves the quality of life for the cows. In addition to the health benefits of eating fresh grass, they get to engage with their herd mates and the environment naturally as they enjoy the outdoors. When carefully managed, grazing can improve or maintain environmental health as well, through increasing soil health, biodiversity, and even carbon sequestration.

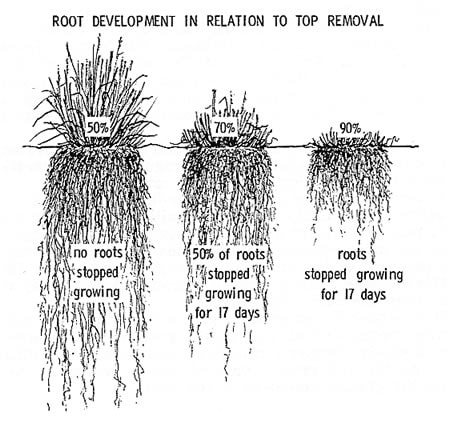

Most pasture plants have evolved to be grazed, and there are dozens of species of grass, fescue and legumes that a cow can choose from. Grazing actually stimulates these plants' growth. Yet, if grazed too short, pasture plants struggle to capture energy from the sun and must move their stored resources in their roots to grow new leaves. Being grazed too short, or too often, time after time will deplete the plant’s energy reserves, leaving an unproductive pasture, and even plant death. However, depending on the season, weather, and the type of plant, grass will grow at variable speeds. In order to maintain the health of the pasture, so that it remains productive in future seasons, the Rivingtons must pay attention to these changes and adjust their grazing plan accordingly. They may give a section of field a longer time to recover based on how quickly it is regrowing, or put the cows in a larger section so the pressure of grazing is spread thinner over the field. The Positive FeedbackBy keeping up this management, the Rivington family and their farm team maintain a positive feedback loop that builds soil and grows nutrient dense grass for their cows. The Rivingtons also enjoy the benefits of not having to purchase and handle certain petroleum based inputs, such as pesticides, herbicides or fertilizer. Practicing grazing means much more time spent in the fields, retrieving cows for milking, moving fencing, or just watching the grass grow - all of which is pretty good exercise (If you don’t believe us, just try racing Bruce up his favorite pasture hill).

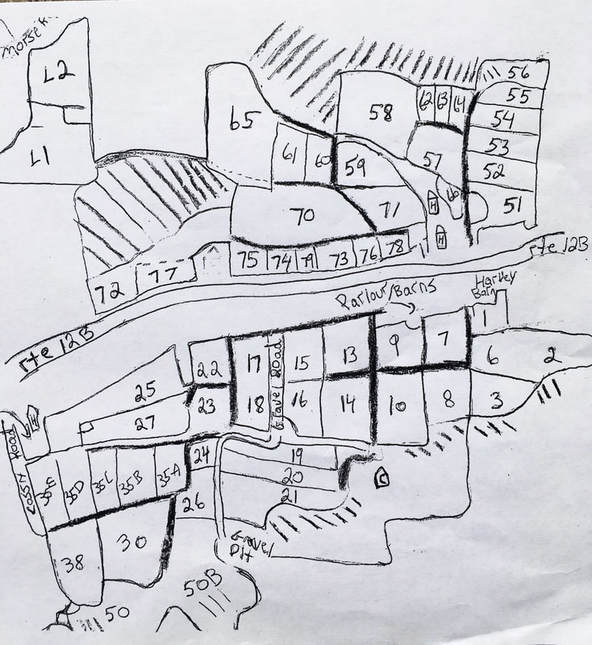

It is true - their cows don’t make as milk as they used to on grain, but the Rivingtons have found a system that is attuned with their values and gives them a lifestyle that suits their family, their farm team, their pastures, their cows, and you, our customers. Don’t just take our word for it, visit the farm on Madison County’s Open Farm Day to experience the joy of a grazing dairy yourself. We’ll have tours, activities, and, of course, plenty of Meadow Butter. If you haven’t learned by now, Kriemhild Dairy is intimately connected with Red Gate Farm, our sole seasonal Meadow Butter supplier. Farmers Bruce and Nancy Rivington own 90% of Kriemhild and have had an essential role in developing our values and guiding the direction of our small agricultural business. In fact, we all would consider being able to access and experience the farm a job perk: we get to interact with their beautiful, and curious, herd of cows, have walking privileges to the rolling pastures, and occasionally get roped into doing some farm work. You, or someone you know, might even be familiar with the farm. Kriemhild and Red Gate Farm often collaborate on farm events to encourage people to engage with the staff and animals who contribute to the production of their food. Red Gate hosted its first Calving Day this year, but many visitors’ first experience of the Farm is during Madison County’s Open Farm Day. Red Gate Farm has been participating in Open Farm Day for the 8 years the event has existed, this year will be no different. But, likely unbeknownst to visitors, 17 years ago, Red Gate’s rolling green pastures looked very different than they do today. From Canada to CNYWhen the Rivington Family moved from their dairy farm in Ontario, Canada to New York, they were on a clear-cut mission: to graze. The Rivingtons wanted to increase the amount their cows could graze, and ultimately switch to seasonal dairying for human and herd wellbeing. Although the Canadian supply management policies promised consistent revenue for Canadian dairy farmers, the system would not accept the variable amount of milk produced by a grazing seasonal dairy. With aspirations of expanding their farm and embracing seasonal grazing, the Rivingtons began to search the Empire State for their new home. Nancy and Bruce visited about 18 different farms hoping to find one that was suited for grazing. Mainly, they were searching for at least 400 acres of contiguous land so as to make it possible to move a herd easily from one pasture to the next. This was more of a challenge than expected. “Real estate agents have real funny definitions of contiguous,” Bruce recalls. It was in the depths of winter when the Rivingtons were introduced to Red Gate Farm. Although the land was buried in snow, the Rivingtons knew it was the farm they were looking for. They bought the farm in 2000. Red Gate Farm was a dairy farm historically, but most of its 512 acres had been in conventionally managed corn and alfalfa crops for almost 3 decades. Although rotating corn and alfalfa crops is an effective practice for those who strive to grow an abundance of those two crops, this type of management can take its toll on the land. Bringing Back The Grass Growing a single or limited amount of crops on the same land quickly depleted the soil of its fertility, making it necessary to apply chemical fertilizers to just as quickly supply the exact amount of nutrients the crop needed. Repeated tilling and cultivating also deteriorated the soil. This practice released soil nutrients into the air and broke up the roots and aggregates that held the soil together, increasing the rate of erosion. Bruce remembers discovering the poor condition of the soils, “When we first bought the farm we had to hunt to find an earthworm.”

Despite its sorry condition, Bruce and Nancy knew the healing effect that grazing could have. So, the Rivingtons gave the Red Gate Farm fields their last tilling ever, only to plant an abundance of perennial grass seeds. Starting with a small herd, they gently grazed and mowed the grass to encourage root growth and carbon sequestration. After 5 years of careful and nurturing management, Red Gate Farm began to resemble the farm we all know today: 737 acres of lush green grass carpeting miles of land speckled with colorful moseying cows grazing at their leisure. Even the section of field burned with pesticides was regenerated, and now is ironically one of their most productive pasture, growing almost exclusively native grasses. “That’s the pasture I like to take people up to, to show them,” Bruce boasts. Land that Doesn't Just Work, But LivesThe Rivingtons did not merely transition Red Gate Farm from one crop to another. They reclaimed land stripped of its nutrients, only able to grow corn and alfalfa, and regenerated it into a thriving ecosystem. Their land not only grows nutrient dense grasses, but it also feeds an expansive community of soil microbacteria and microfauna, acts as a habitat for wildlife, and even mitigates greenhouse grasses.

Although this happened long before Kriemhild was established, we would not exist without Red Gate Farm, so we embrace it as part of our story. We hope to help other farmers tell their own similar stories as we grow. Until then, you can visit Red Gate Farm on July 29th as we celebrate Madison County’s Open Farm Day. It’ll be a great chance to learn more about how agriculture can be a pivotal point of community, nutritional, and environmental health. How about both?April 22 is earth day, and per Earth Day tradition, many folks will feel inspired to plant a tree, and they should. In a time of drastically changing climate, planting trees is one way of combating the excess of greenhouse gases trapping heat in the atmosphere. Through photosynthesis, trees and other plants pull carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and convert it into sugar, cellulose, and other carbon-containing carbohydrates that they use for nourishment and growth. This natural process is called carbon sequestration. Although trees are famous for their carbon sequestering abilities, it is actually soil that is the largest terrestrial reservoir of carbon. Soils contain approximately 3/4 of the carbon pool on land — three times more than the amount stored in living plants and animals. This is great news, but, how does carbon come to be stored in soil? The answer: through plant roots. When plants convert CO2 into food for themselves, they are also creating food for microorganisms in the soil through their root exudate. These microorganisms eat and defecate, directly adding organic carbon to the soil and increasing its organic matter. Trees are impressive exemplars of biomass, many of which grow taller and older than any human. However, in reality the greatest amount of carbon is sequestered in the soil of grazing lands. While trees store most of their carbon in vegetation that eventually dies and rots (re-releasing the carbon), carbon sequestered by grazing lands is more readily transferred into the soil itself, where it can be permanently stored (1). Among the types of agricultural land, grazing land has the highest ability to sequester carbon, partly because its soil is left intact as it is used. Although many crop farms now use practices to keep soil covered, carbon is lost to the atmosphere every time cropland soil is disturbed via tilling and in some cases harvesting. Our soils have lost more than half their carbon over the last 200 years due to common crop farming practices. There is a long-held misconception that pasturing livestock only results in overgrazing and desertification of grasslands. However, if done with proper management, the use of grazing lands with domestic livestock can play a significant role in mitigating climate change. Researchers have estimated that it is possible for 29.5-110 million metric tons of carbon to be sequestered annually in the grazing lands in the United States (2). Grass has evolved to be grazed. When grass is grazed by an herbivore, it stimulates the plant to begin a phase of rapid biomass production. This means more photosynthesis and thus more carbon sequestrated into the soil. In the absence of grazing, or well timed mechanical harvesting, grass merely grows to a certain maturity, becomes senescent and dies. Dead grass will decompose, but the amount of carbon it adds to soil is nowhere near the amount the cycle of grazing and regrowth can sequester. Nothing can mimic the natural interaction between plants and grazing animals. When overgrazing occurs, the grass does not have enough time to regrow, so it drains the energy reserves in its roots. This results in shorter and shorter roots that are unable to hold the soil together or feed the resident microorganisms. Proper grazing management allows grass to recuperate after a calculated grazing period on a specific area by a certain number of animals. The livestock are moved rotationally around the pasture in paddocks, and may not re-visit a previous paddock for weeks at a time. This management is very healthy for the soils, and it is beneficial for the animals subsisting on them. There are several different types of management strategies that take a pasture’s rest and regrowth into consideration such as Management Intensive Rotational Grazing, Mob Grazing, and Holistic Grazing Management, to name a few. Well managed grazing land could rival the intensity of passive soil carbon accumulation of native ecosystems. As a triple-bottom-line business that equally weights Environment, Community, and Profit in our operation, we at Kriemhild take great interest in the grazing management of our producers. We believe that grazing is important nutritionally for livestock animals and the food they produce, but it also has the ability to affect profound and far-reaching positive environmental impact. If all of the countries on earth committed to increasing their soil carbon by just 0.4% each year, the global community could store 75% of our annual industrial greenhouse emissions. The way that farmers choose to use and manage agricultural grazing lands, and the practices consumers support thru our purchases, can and do shape our global environment thru local ecology.

So, don’t hesitate to plant your tree on earth day. Just remember this as well: when you choose purchase our Meadow Butter or Crème Fraîche, you are choosing to support over 1500 acres of active soil carbon sequestration; and that’s one more way you can influence global change thru small, local action. Cited Sources: (1) Schuman, G.E., D.R. LeCain, J.D. Reeder, and J.A. Morgan. 2001. “Carbon Dynamics and Sequestration of a Mixed-Grass Prairie as Influenced by Grazing.” In Soil Carbon Sequestration and the Greenhouse Effect, special publication no. 57, edited by R. Lal, 67-75. Madison, WI: Soil Science Society of America. (2) Follett, R.F., J.M. Kimble, and R. Lal. 2001. The Potential of U.S. Grazing Lands to Sequester Carbon and Mitigate the Greenhouse Effect. Boca Raton, FL: Lewis Publishers |

As the Butter Churns

Author: Ellen Fagan and Victoria PeilaCategories

All

Archives

November 2019

|

Where our HEart is

|

FOLLOW US |

what our customers are saying"Thank you! Even though I'm 5 hours away...I can't live without you. Got my shipment today.

#kriemhildbutterlove" -- Jennifer in Mystic, Connecticut |

Copyright 2020 © Kriemhild Dairy Farms, LLC

RSS Feed

RSS Feed