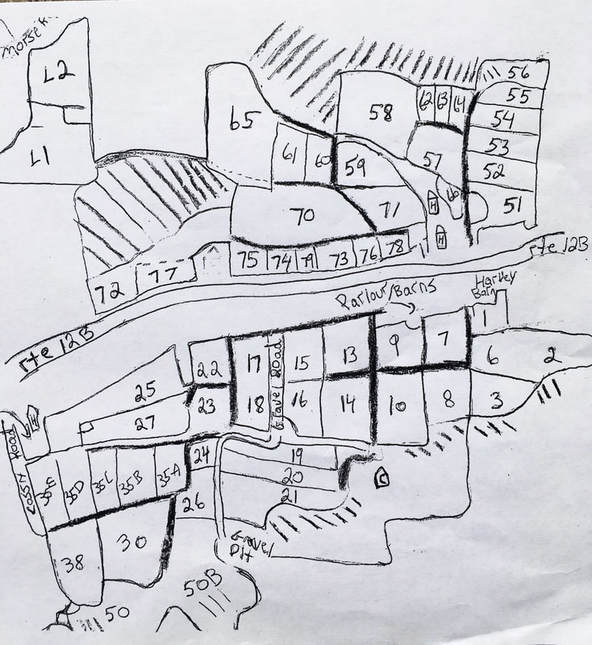

It Took Some Convincing...Bruce and Nancy Rivington moved their entire farm and family of six from Ontario, Canada to Hamilton, NY in order to give their cows more chances to graze. But, just as Red Gate Farm wasn’t always a grazing farm , Bruce and Nancy were not always graziers. “I kind of made fun of it, [grazing]” Bruce explains, “It seemed stupid, why’d you want to do that when you could just… get more milk production by bringing the feed to the cows?” In Canada, the Rivingtons were content with growing, cultivating, and harvesting crops for the purpose of feeding to their herd. They had a plenty high milk production per cow. Why would they want to give up something they were good at? It wasn’t until they attended a talk by Sonny Golden, a grazing and nutrition specialist from Springfield, PA, that the Rivingtons began to examine their management choices. “He says, ‘You plant corn. What grows? Grass. You plant soybeans. What grows? Grass. You plant barley. What grows? Grass! Why aren’t you growing grass?!’ Which made a lot of sense.” Bruce reminisced. Bruce and Nancy realized they were producing a large quantity of milk, but the costs of such high production were taking their toll. As Bruce remembers, “We were hauling all the feed to the cows, but we were wearing out ourselves, our cows, the machinery, the barn.” Therefore, the Rivingtons decided to try to work within the naturalized system of pasture and ruminant animals, instead of against it, and began practicing grazing in 1994.

Grazing has more than just financial benefits. It improves the quality of life for the cows. In addition to the health benefits of eating fresh grass, they get to engage with their herd mates and the environment naturally as they enjoy the outdoors. When carefully managed, grazing can improve or maintain environmental health as well, through increasing soil health, biodiversity, and even carbon sequestration.

Most pasture plants have evolved to be grazed, and there are dozens of species of grass, fescue and legumes that a cow can choose from. Grazing actually stimulates these plants' growth. Yet, if grazed too short, pasture plants struggle to capture energy from the sun and must move their stored resources in their roots to grow new leaves. Being grazed too short, or too often, time after time will deplete the plant’s energy reserves, leaving an unproductive pasture, and even plant death. However, depending on the season, weather, and the type of plant, grass will grow at variable speeds. In order to maintain the health of the pasture, so that it remains productive in future seasons, the Rivingtons must pay attention to these changes and adjust their grazing plan accordingly. They may give a section of field a longer time to recover based on how quickly it is regrowing, or put the cows in a larger section so the pressure of grazing is spread thinner over the field. The Positive FeedbackBy keeping up this management, the Rivington family and their farm team maintain a positive feedback loop that builds soil and grows nutrient dense grass for their cows. The Rivingtons also enjoy the benefits of not having to purchase and handle certain petroleum based inputs, such as pesticides, herbicides or fertilizer. Practicing grazing means much more time spent in the fields, retrieving cows for milking, moving fencing, or just watching the grass grow - all of which is pretty good exercise (If you don’t believe us, just try racing Bruce up his favorite pasture hill).

It is true - their cows don’t make as milk as they used to on grain, but the Rivingtons have found a system that is attuned with their values and gives them a lifestyle that suits their family, their farm team, their pastures, their cows, and you, our customers. Don’t just take our word for it, visit the farm on Madison County’s Open Farm Day to experience the joy of a grazing dairy yourself. We’ll have tours, activities, and, of course, plenty of Meadow Butter.

0 Comments

How about both?April 22 is earth day, and per Earth Day tradition, many folks will feel inspired to plant a tree, and they should. In a time of drastically changing climate, planting trees is one way of combating the excess of greenhouse gases trapping heat in the atmosphere. Through photosynthesis, trees and other plants pull carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and convert it into sugar, cellulose, and other carbon-containing carbohydrates that they use for nourishment and growth. This natural process is called carbon sequestration. Although trees are famous for their carbon sequestering abilities, it is actually soil that is the largest terrestrial reservoir of carbon. Soils contain approximately 3/4 of the carbon pool on land — three times more than the amount stored in living plants and animals. This is great news, but, how does carbon come to be stored in soil? The answer: through plant roots. When plants convert CO2 into food for themselves, they are also creating food for microorganisms in the soil through their root exudate. These microorganisms eat and defecate, directly adding organic carbon to the soil and increasing its organic matter. Trees are impressive exemplars of biomass, many of which grow taller and older than any human. However, in reality the greatest amount of carbon is sequestered in the soil of grazing lands. While trees store most of their carbon in vegetation that eventually dies and rots (re-releasing the carbon), carbon sequestered by grazing lands is more readily transferred into the soil itself, where it can be permanently stored (1). Among the types of agricultural land, grazing land has the highest ability to sequester carbon, partly because its soil is left intact as it is used. Although many crop farms now use practices to keep soil covered, carbon is lost to the atmosphere every time cropland soil is disturbed via tilling and in some cases harvesting. Our soils have lost more than half their carbon over the last 200 years due to common crop farming practices. There is a long-held misconception that pasturing livestock only results in overgrazing and desertification of grasslands. However, if done with proper management, the use of grazing lands with domestic livestock can play a significant role in mitigating climate change. Researchers have estimated that it is possible for 29.5-110 million metric tons of carbon to be sequestered annually in the grazing lands in the United States (2). Grass has evolved to be grazed. When grass is grazed by an herbivore, it stimulates the plant to begin a phase of rapid biomass production. This means more photosynthesis and thus more carbon sequestrated into the soil. In the absence of grazing, or well timed mechanical harvesting, grass merely grows to a certain maturity, becomes senescent and dies. Dead grass will decompose, but the amount of carbon it adds to soil is nowhere near the amount the cycle of grazing and regrowth can sequester. Nothing can mimic the natural interaction between plants and grazing animals. When overgrazing occurs, the grass does not have enough time to regrow, so it drains the energy reserves in its roots. This results in shorter and shorter roots that are unable to hold the soil together or feed the resident microorganisms. Proper grazing management allows grass to recuperate after a calculated grazing period on a specific area by a certain number of animals. The livestock are moved rotationally around the pasture in paddocks, and may not re-visit a previous paddock for weeks at a time. This management is very healthy for the soils, and it is beneficial for the animals subsisting on them. There are several different types of management strategies that take a pasture’s rest and regrowth into consideration such as Management Intensive Rotational Grazing, Mob Grazing, and Holistic Grazing Management, to name a few. Well managed grazing land could rival the intensity of passive soil carbon accumulation of native ecosystems. As a triple-bottom-line business that equally weights Environment, Community, and Profit in our operation, we at Kriemhild take great interest in the grazing management of our producers. We believe that grazing is important nutritionally for livestock animals and the food they produce, but it also has the ability to affect profound and far-reaching positive environmental impact. If all of the countries on earth committed to increasing their soil carbon by just 0.4% each year, the global community could store 75% of our annual industrial greenhouse emissions. The way that farmers choose to use and manage agricultural grazing lands, and the practices consumers support thru our purchases, can and do shape our global environment thru local ecology.

So, don’t hesitate to plant your tree on earth day. Just remember this as well: when you choose purchase our Meadow Butter or Crème Fraîche, you are choosing to support over 1500 acres of active soil carbon sequestration; and that’s one more way you can influence global change thru small, local action. Cited Sources: (1) Schuman, G.E., D.R. LeCain, J.D. Reeder, and J.A. Morgan. 2001. “Carbon Dynamics and Sequestration of a Mixed-Grass Prairie as Influenced by Grazing.” In Soil Carbon Sequestration and the Greenhouse Effect, special publication no. 57, edited by R. Lal, 67-75. Madison, WI: Soil Science Society of America. (2) Follett, R.F., J.M. Kimble, and R. Lal. 2001. The Potential of U.S. Grazing Lands to Sequester Carbon and Mitigate the Greenhouse Effect. Boca Raton, FL: Lewis Publishers |

As the Butter Churns

Author: Ellen Fagan and Victoria PeilaCategories

All

Archives

November 2019

|

Where our HEart is

|

FOLLOW US |

what our customers are saying"Thank you! Even though I'm 5 hours away...I can't live without you. Got my shipment today.

#kriemhildbutterlove" -- Jennifer in Mystic, Connecticut |

Copyright 2020 © Kriemhild Dairy Farms, LLC

RSS Feed

RSS Feed