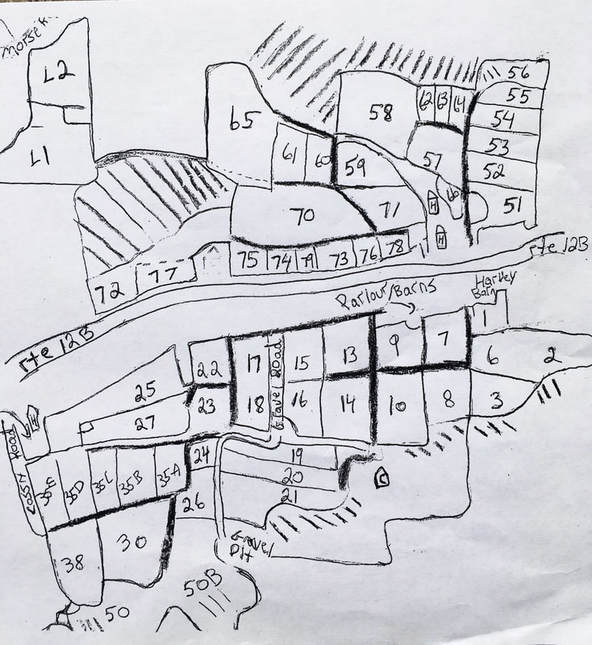

It Took Some Convincing...Bruce and Nancy Rivington moved their entire farm and family of six from Ontario, Canada to Hamilton, NY in order to give their cows more chances to graze. But, just as Red Gate Farm wasn’t always a grazing farm , Bruce and Nancy were not always graziers. “I kind of made fun of it, [grazing]” Bruce explains, “It seemed stupid, why’d you want to do that when you could just… get more milk production by bringing the feed to the cows?” In Canada, the Rivingtons were content with growing, cultivating, and harvesting crops for the purpose of feeding to their herd. They had a plenty high milk production per cow. Why would they want to give up something they were good at? It wasn’t until they attended a talk by Sonny Golden, a grazing and nutrition specialist from Springfield, PA, that the Rivingtons began to examine their management choices. “He says, ‘You plant corn. What grows? Grass. You plant soybeans. What grows? Grass. You plant barley. What grows? Grass! Why aren’t you growing grass?!’ Which made a lot of sense.” Bruce reminisced. Bruce and Nancy realized they were producing a large quantity of milk, but the costs of such high production were taking their toll. As Bruce remembers, “We were hauling all the feed to the cows, but we were wearing out ourselves, our cows, the machinery, the barn.” Therefore, the Rivingtons decided to try to work within the naturalized system of pasture and ruminant animals, instead of against it, and began practicing grazing in 1994.

Grazing has more than just financial benefits. It improves the quality of life for the cows. In addition to the health benefits of eating fresh grass, they get to engage with their herd mates and the environment naturally as they enjoy the outdoors. When carefully managed, grazing can improve or maintain environmental health as well, through increasing soil health, biodiversity, and even carbon sequestration.

Most pasture plants have evolved to be grazed, and there are dozens of species of grass, fescue and legumes that a cow can choose from. Grazing actually stimulates these plants' growth. Yet, if grazed too short, pasture plants struggle to capture energy from the sun and must move their stored resources in their roots to grow new leaves. Being grazed too short, or too often, time after time will deplete the plant’s energy reserves, leaving an unproductive pasture, and even plant death. However, depending on the season, weather, and the type of plant, grass will grow at variable speeds. In order to maintain the health of the pasture, so that it remains productive in future seasons, the Rivingtons must pay attention to these changes and adjust their grazing plan accordingly. They may give a section of field a longer time to recover based on how quickly it is regrowing, or put the cows in a larger section so the pressure of grazing is spread thinner over the field. The Positive FeedbackBy keeping up this management, the Rivington family and their farm team maintain a positive feedback loop that builds soil and grows nutrient dense grass for their cows. The Rivingtons also enjoy the benefits of not having to purchase and handle certain petroleum based inputs, such as pesticides, herbicides or fertilizer. Practicing grazing means much more time spent in the fields, retrieving cows for milking, moving fencing, or just watching the grass grow - all of which is pretty good exercise (If you don’t believe us, just try racing Bruce up his favorite pasture hill).

It is true - their cows don’t make as milk as they used to on grain, but the Rivingtons have found a system that is attuned with their values and gives them a lifestyle that suits their family, their farm team, their pastures, their cows, and you, our customers. Don’t just take our word for it, visit the farm on Madison County’s Open Farm Day to experience the joy of a grazing dairy yourself. We’ll have tours, activities, and, of course, plenty of Meadow Butter.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

As the Butter Churns

Author: Ellen Fagan and Victoria PeilaCategories

All

Archives

November 2019

|

Where our HEart is

|

FOLLOW US |

what our customers are saying"Thank you! Even though I'm 5 hours away...I can't live without you. Got my shipment today.

#kriemhildbutterlove" -- Jennifer in Mystic, Connecticut |

Copyright 2020 © Kriemhild Dairy Farms, LLC

RSS Feed

RSS Feed